Steamboat Round the Bend

Irvin S. Cobb

Irvin S. Cobb as Captain Eli

Inside the Pride of Paducah pilot house (l-r): Doctor John, Captain Eli, and Pilot Mink.

DOC - Morning, Captain Eli.

ELI - Hello, Doc. Make yourself at home.

(Doc pulls the whistle cord)

ELI - Say, what in thunder are you doin'?

DOC - I'm just teaching you how to salute my boat. The CLAREMORE QUEEN. Look at her layin' over there.

ELI - Yeah. Give her two more toots.

DOC - Say, that's four. That's a double salute.

ELI - No. Just honoring the unburied dead, that's all.

DOC - Don't try to poke any fun at that. Duke and I just bought it. We saved up every nickel we got to get that boat.

ELI - Duke? That's your nephew, ain't it?

DOC - You bet your life. And he's a great boy, Duke.

ELI - I thought he was pilot on the MEMPHIS GIRL.

DOC - Well, he was. He's the main pilot on there. But not no more. He's making his last trip and then he's comin' right on there with me.

ELI - You stick to doctoring. You ain't no steamboat man.

[ELI to MINK, the pilot]: Cramp her, Mink. Cramp her. I'll take her, Mink.

Well, admittin' Duke's a pretty good boy, what could you do on a steamboat?

DOC - Well, I'm just gonna sit up in the pilot house and toot the whistle and listen to that old river sing.

ELI - The way you brag, I suppose you're fixin' to stick that old apple crate yonder in the big race to Baton Rouge this summer.

DOC - I never had thought of that. But that's an idea at that. You know, the CLAREMORE QUEEN won that race in '84. And with Duke as pilot, I'll bet she could win it again.

ELI - I suppose you'd like to bet your boat against my boat on the result of that race, huh?

DOC - Well, I don't know. Well, I'll bet you at that. I'll bet you.

ELI - You made yourself a bet and lost yourself a steamboat.

Signing up for the Race

Close-up of Rogers and Cobb discussing terms of the steamboat race indoors in a waterfront building a few minutes before the race was to start.

CLAY - (the official signing up Captains for the steamboat race):

Now, you captains ain't gonna start until the cannons go off. Then you can do what you please. The first boat that reaches Baton Rouge wins the race as well as the prize from the governor's own hand.

DOC - Here, Clay, hey, what's the idea of flaggin' me in here?

CLAY - Sorry, Doc, but you know the rules of the race.

DOC - I'm not in the race. I'm tryin' to get to Baton Rouge.

CLAY - Oh, no, you ain't, either.

ELI - I knowed you'd try to back out of that race. Scared you'll lose that old chicken coop.

DOC - Chicken coop, nothin'. You still wanna bet the PRIDE OF PADUCAH against the CLAREMORE QUEEN?

ELI - As I recall, that was the terms of the bet, unless you're crawfishing. Winner takes both boats.

DOC - Is that so? Well, I'll just take you up on that. I'll bet you my boat against yours, whole hog or none with me. I'll go in the race. It'll slow me up going to Baton Rouge, but I'll go in. What time do we start?

CLAY - Sergeant Benson shoots off that cannon in five minutes.

DOC - Now, wait. Give me time to load on some firewood. I'm purt' near out.

ELI - Same ol' Pokey-hontas. Always full of alibi's. You couldn't win if you put wings on!

CLAY - She starts when the gun goes off. That's the rules. You fellas better hurry and get on your boats.

Irvin S. Cobb is holding a mint julep in his mit . . . wonder if it was the real thing or a Shirley Temple? This documents what happened just before the race started with Eli tormenting Doc from inside the PRIDE OF PADUCAH's pilot house with Pilot Mink laughing in the background.

Eli's insult that he's laying on Doc:

"Hey, Doc, better hug close to shore! No tellin' when that ol' honey wagon's gonna sink."

Flames blaze from the smokestaks of the Pride of Paducah in the heat of the race.

All dialogue in this section is derived from the "S.S. Springfield Movie Script UK - Steamboat Round the Bend" page springfieldspringfield.co.uk or scripts.com.

Further information about Irvin S. Cobb

Irvin S. Cobb (Cap'n Eli) was inducted into Kentucky writers hall of fame in 2017

Kentucky Writers

Hall of Fame

Inductees

2017

carnegiecenterlex.org

Irvin S. Cobb (1876-1944)

Paducah native Irvin Shrewsbury Cobb was perhaps one of Kentucky's most versatile writers and personalities from the 1920s to 1940s. Journalist, essayist, syndicated columnist, novelist, poet, script writer, actor, storyteller, humorist, lecturer, and Academy Award host were among the many roles Cobb played in a career that spanned over 50 years. As a journalist, he wrote for the Paducah Daily News, Louisville Evening Post, The New York Evening Sun, The New York Evening World, Cincinnati Post, and Saturday Evening Post.

Cobb was anti-prohibition and a prominent member of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. The Association is credited with the demise of Prohibition in 1934. His crusade prompted a famous novel Red Likker (1929), which was touted the only American novel ever devoted completely to the whiskey industry. The novel is set in post-Civil War and focuses upon an old Kentucky family headed by Colonel Atilla Bird who operates Bird & Son distillery until Prohibition closes it in 1920. Cobb once lamented that prior to Prohibition, "Men of all stations of life drank freely and with no sense of shame in their drinking. Bar-rail instep, which is a fallen arch reversed, was a common complaint among us."

Cobb authored 69 published books, including novels, short stories, essays, memoirs, and collections of newspaper and magazine articles. His first book Talks with the Fat Chauffer debuted in 1909 and his last was Piano Jim and the Impotent Pumpkin Vine in 1950. Although many of his works had a serious bent, several were comedic and infused with his rural Kentucky hyperbolic wit and sense of humor. Three of his short stories "All American Storytellers," "Peck's Bad Boy," and "Pardon my French" were adapted to the movie screen in 1921. He continued writing for the film industry well into the 1930s.

"The Woman Accused" starring Cary Grant and Nancy Carroll was released in 1933. He paired with director John Ford and Fox Studios, who made "Judge Priest" in 1934, which starred Will Rogers and included Cobb in a small acting part. This was the most elaborate of Ford's Cobb films and was based on three specific stories: "The Sun Shines Bright," "The Mob from Massac," and "The Lord Provides." Ford cast Charles Winninger as Judge Billy Priest. In the interim, director James Whale released "Showboat" in 1936, starring Irene Dunn, Alan Jones, and Charles Winninger. "The Sun Shines Bright," was released posthumously by Republic Studios in 1953. Cobb appeared in ten movies between 1932 and 1938. His major roles were in "Pepper" (1936) and "Hawaii Calls" (1938). He was selected to host the 6th Academy Awards in 1935.

Critic H.L. Mencken compared Cobb to Mark Twain. He also garnered respect from the renowned Joel Chandler Harris and others, but Cobb's literary reputation faded rapidly at the turn of the 1940s. Many critics have suggested that Cobb writing was caught in the wake of post-Civil War when "His benign vision of the rural South no longer seemed relevant or accessible amid the rising of the civil rights movement and the call for an end to segregation." Cobb's style, like many of the local color era writers grew increasingly dated and out-of-step with contemporary writing. After a period of declining health, Cobb died on March 10, 1944 and is buried in the Paducah, Kentucky Oak Grove Cemetery.

Irvin S. Cobb

imdb.com

JUNE 23, 1876 - MARCH 11, 1944

Irvin S. Cobb, novelist and dramatist who acted in occasional US films of both silent and sound eras.

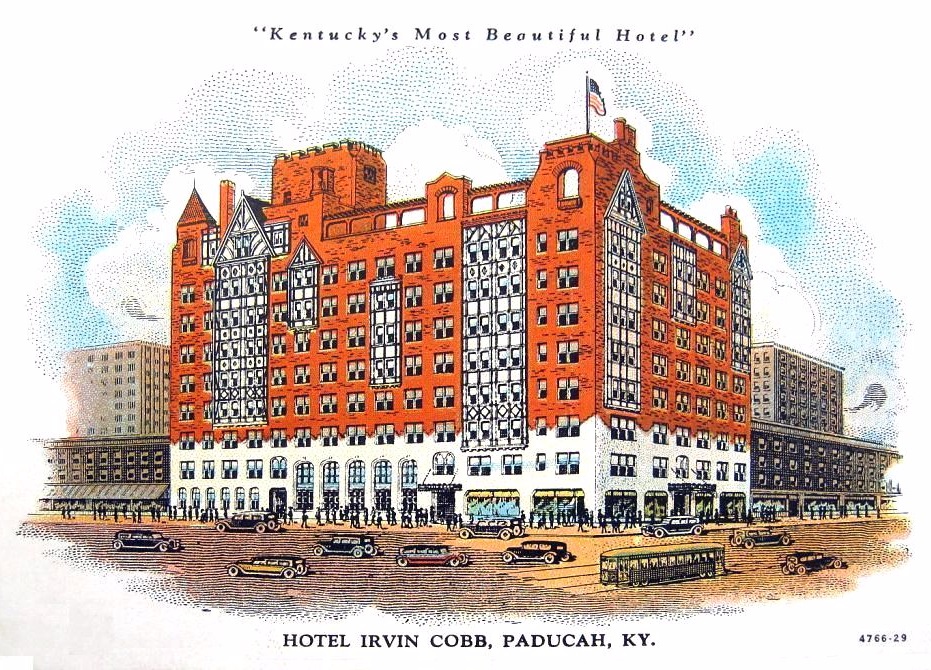

In 1916 when Cobb was 40 years old, and 19 years before he co-starred in 1935 at age 59 with Will Rogers in STEAMBOAT ROUND THE BEND Irvin S. Cobb was already the local hero of Paducah, Kentucky where a local cigar company and its product were named for him. Paducah's HOTEL IRVIN COBB was built between 1927 and 1929 and is now an apartment house.

waymarking.com

The HOTEL IRVIN COBB was constructed between 1927-29 during the era of a rollicking economy at a cost of $400,000. During its period of operation, the COBB drew more state conventions than any other place in western Kentucky before the development of state park resort centers at Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake. - The Courier-Journal, Louisville, October 29, 1974.

Due to its reputation as one of the South's finest hotels, all Paducah civic clubs met there for many years, and the eighth-floor's Governor's Suite played host to numerous theatrical and political figures. Even during the Depression, the Cobb Hotel prospered. At its peak, formal attire was required for the evening in the dining room, and during warm weather renowned orchestras provided music for roof terrace dances—crowds gathering on the streets below for listening pleasure." - National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form paducahky.gov

Paducah, originally known as Pekin, was settled around 1815. Settlers were attracted to the community due to its location at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers.

The community was inhabited by a mix of Native Americans and Europeans who lived harmoniously, trading goods and services.

In 1827, William Clark, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Mississippi-Missouri region, arrived in Pekin with a title deed to the land he now owned, which was issued by the United States Supreme Court. Clark most likely took stock of the settlers that had arrived at some point before himself, and offered the land for purchase, so they could occupy it with title in their name. If they did not choose to purchase the right to occupy the land, they most likely relocated to another domicile. The town was platted out and named in honor of the largest nation of Native Americans that ever roamed North America, the Padouca Indians. Lewis and Clark had made acquaintance with many of them while on their trek west.

A letter written by Clark to his son clearly states the reason for the naming of the town. (A facsimile of the letter and the original Paducah maps are on display at the Market House Museum in Paducah.)

The community was incorporated in 1830. Paducah thrived due to its port facilities along the waterways that were used by steamboats. A factory that manufactured red bricks was established and a foundry for making rail and locomotive components was built, ultimately contributing to a river and rail industrial economy.

In 1856, Paducah was chartered as a city. The community continued to capitalize on its geographic location by becoming the site of dry dock facilities for steamboats and towboats and, in turn, headquarters for various barge line companies. Paducah also became an important railway hub for the Illinois Central Railroad (ICRR) due to its proximity to the coal fields in Kentucky and Illinois.

In 1937, the Ohio River at Paducah rose over its 50-foot flood stage. The flood was considered to be the worst natural disaster in Paducah's history. As a result of the flood, the United States Army Corps of Engineers built a flood wall to replace the earthen levee that had once been in place.

In Cobb's 1942 memoirs EXIT LAUGHING he wrote a colorful history of steamboating at Paducah.

EXIT LAUGHING

by Irvin S. Cobb (1876 - 1944)

1942 Garden City Publishing

Pages 75 - 79

There never was but one Paducah; there never will be but one Paducah. So Paducah's loyal, boastful children claim. I'm claiming it for her, too.

I was well along in my teens before the inter-related steamboating interests ceased to dominate the picture. Until then the river either touched the lives or furnished the living for nearly every household and tragically took its toll from them too.

From the very beginnings, when a cluster of log huts sprang up about a wood yard and a hand-ferry at the mouth of the Tennessee, this had been true. Indeed there might never have been any town here at all were it not for three great rivers funneling together within a stretch of fourteen miles to feed into the nearby Mississippi a flow almost as great as the mighty mother stream's. Or if there were a town decreed it could have found its place in the range of low hills farther back, rather than along the flattened lands facing the low banks where floods could menace it and, on occasion, devastate it.

On a single day in the flush years I've seen ten or twelve steamers, lordly deep-bellied sidewheelers and limber slender sternwheelers, ranked two or three abreast at the landing; and the inclined wharf, from the dry-docks almost up to the marine ways, literally blocked off with merchandise incoming or freight outgoing-cotton in bales, tobacco in hogsheads, peanuts in sacks, whisky in barrels and casks, produce and provender of a hundred sorts. Transfer boats, and ferryboats and fussy tugs and perhaps a lighthouse tender or a government "snag boat" would be stirring about; both of the squatty scow-like wharf boats bulging with perishable stuffs; "coonjining" rousters bearing incredible burdens and still able to sing under their loads, swearing mates and sweating "mud-clerks"; drays and wagons and hacks and herdics (a "herdic" was a low-hung public carriage of the late 19th-century with a back entrance and seats along the sides) rattling up and down the slants; twin lanes of travelers dodging along the crowded gangplanks; a great canopy of coal smoke darkening the water front; a string band playing on the guards of some excursion steamer; maybe, for good measure, a calliope blasting away from the top deck of a visiting showboat such as French's New Sensation, or Robinson's Floating Palace, or Old Man Price's; scape pipes shrilling and engine bells jangling; and, over-riding all lesser sounds, the hoarse bellow of the whistle between this or that pair of lofty stacks as one of the packets gave notice of her departure.

Barring flood times with which no human hands could cope, only midsummer brought a slackening-off in these profitable ramifications; not always though but frequently. Those years the channels shoaled and kept on shoaling until the bars stood up high, like great turtles bleaching their backs in the heat, and the "chutes" went bone-dry and in the formerly convenient "cut-offs" only the catfish and the gars and the buffalo fish might navigate - and sometimes even they got sunburned. Regular liners hunted the bank then and stayed there, and the owners fumed and prayed for torrential rains at the headwaters and the pessimists amongst them lamented that in this accursed business it was always either a feast or a famine; while the crews temporarily transferred to the "mosquito fleets," these being chartered boats of such skimpy draft that, as the saying went, any one of them could run on a heavy dew. But let a general break occur in the weather and the lean pickings would be at an end in a jiffy.

And pretty soon then, coming on the crest of the fall rise, the big towboats from the "Head of the Hollow" would go chugging by out in mid-current, each one shoving acres of loaded coal barges before her squared bows, and their yawls racing in for provisions and supplies, then racing back out to overtake the plodding convoys. This also was an approved season for the lumbermen to drift down the Tennessee with their huge rafts, and the rafts would be broken up and the timbers imprisoned by the thousands within the "gunnels" of the sawmills and the woodworking plants along shore. Some of the raftsmen got impounded too-in the calaboose. For with all that good log money in their pockets they went on most gorgeous sprees.

Later, when ice had locked the Missouri and the Upper Mississippi and the Upper Ohio, the inner two-mile stretch of Owen's Island, for all the way between the lower towhead and the farther tip where it aimed at Livingston Point, would be lined and often in favored anchorage double-lined and triple-lined with all fashion of craft brought hither to "lay up" in the safest winter haven for a thousand miles of tributary waterways - the famous Duck's Nest. And over on the town side, snuggled amongst the protecting fringes of willow and cypress where Island Creek emptied in, would be a jumble of "shanty boats" and "joe boats" populated by amphibious guilds: fishermen and trappers and market-gunners; poachers and foragers; cobblers and tinkers; peddlers, fortune tellers, "root-and-herb doctors," itinerant preachers of curious creeds; ginseng-diggers, tie-hackers; mussel-dredgers; owners of "tintype galleries" and penny peep shows; floating junk collectors, Cheap Johns and Jacks-of-all-trades, dealers in live bait and in notions and knick-knacks and dubious patent medicines, all hibernating together until spring sent them voyaging upstream or down, with their babies and their dogs, their trotlines and their gill nets, to spend nine months of pure gypsying.

Now water-farers, whether the water be salt or fresh, have always been a separate subspecies, more picturesque than plodding stay-at-homes. It was so with us. Our deck hands were swaggering bravos who talked a strange professional jargon and counted themselves a hardier breed and a more reckless one than their brethren ashore. Our mates notoriously were trigger-fingered. Once aboard, masters and pilots became imperious overlords. It was a chancy calling which these mariners of ours pursued and they carried themselves accordingly. If you couldn't snap your fingers in the face of danger you couldn't qualify. For the river, which gave these men their daily bread, was not alone an uncertain provider but a most fickle mistress. There was no taming her. She was like a snake which wriggled sluggishly along in seasons of drought, only to strike, like a snake, when the onrushing freshets put a twisting, swirling viciousness into the swollen coils. Moreover, what with boilers to blow up and snags to rip the bottoms out of lightly built hulls and fires to turn the matchwood upper structures into flaming furnaces and some quick fierce storm to capsize a heavy laden carrier, it was a small wonder - it was no wonder at all - that the lines of graves in the cemeteries were punctuated with the headstones of those who had lived by the river and by it had lost their lives.

Sometimes the same surname recurred on the slabs. For there was a clannishness, a sort of freemasonry about the whole thing. If your father "followed the river" it rather was expected that you, growing up, would travel the same lane. For a typical example take my father's case. As far back as 1818 his grandfather, shrewd and forehanded Vermont Irishman that he was, had given up keelboating to buy part ownership in the first steam-driven craft that plied the Cumberland River. At the peak of the family fortunes my father's father controlled a small fleet of short-haul steamers, manned largely by his own slaves. And my father himself was a steamboatman with a master's license and, for the better part of his life, a place as traffic manager of a navigation company, so that the unbroken span of operations for his people extended through upwards of seventy years.

So it went. If you were a Rollins or a Pell or a Cole or a Beard you almost inevitably were destined to be a pilot. There were eleven Pells who had held pilots' papers, including "Yankee" Pell who, against his private principles, had been pressed to steer a Federal gunboat, and "Rebel" Pell who quit his wheelhouse to fight uncle' Forrest; Slick Pell who was smooth-shaven and Curly Pell who wasn't; Big Ed and Little Ed, Old Charley and Young Charley and Young Charley's Charley, all sizes and ages, but all Pells. The Dunns were usually were pursers, just as a young Hoey or a young McMeekin was a potential mate, and a Dozier was destined for an engineer's berth. An Owen inevitably would be in the ferryboat traffic. Through three generations the Fowlers were steamboat owners- the name was renowned from New Orleans to Pittsburgh, for they also owned wharf boats and a "boat store." And the lives of two of them were sacrificed to the greedy waters. One, before my time, burned to death after a boiler exploded and the other, a handsome promising lad serving his apprenticeship as a junior officer, was drowned doing rescue work when a sinking occurred in the nighttime.

My mother's eldest sister was married to one of these Fowlers, who died fairly young from the after-effects of the privations he had endured as a trooper in Morgan's Cavalry; hence, submitting to a cruel edict then prevalent, she wore the mourning garb ordained for widows for almost half a century until the end of her days. Those black folds cloaked a lady whose tongue was a lancet tipped with a mordant and a devastating humor. Most witty women, I've noticed, do carry chilled-steel barbs in their wit. My Aunt Laura stung her victims in a mortal spot and left them where they fell. In her circle of intimates was a rather elderly spinster who so flutteringly was taken up with good deeds and club activities that she sometimes overlooked the soap-and-water attentions which a less zealous gleaner in the grape arbors of the Lord might have bestowed upon herself. In her absence-which was fortunate for all concerned-someone referred to this devoted Dorcas as being wishy-washy. Up spoke Aunt Laura. "She may be wishy," she stated briskly, "but God in Heaven knows the woman is not washy."

Return to Steamboat Round the Bend Program

All captions provided by Dave Thomson, Steamboats.com primary contributor and historian.