Steamboat Snag Boats, page 2

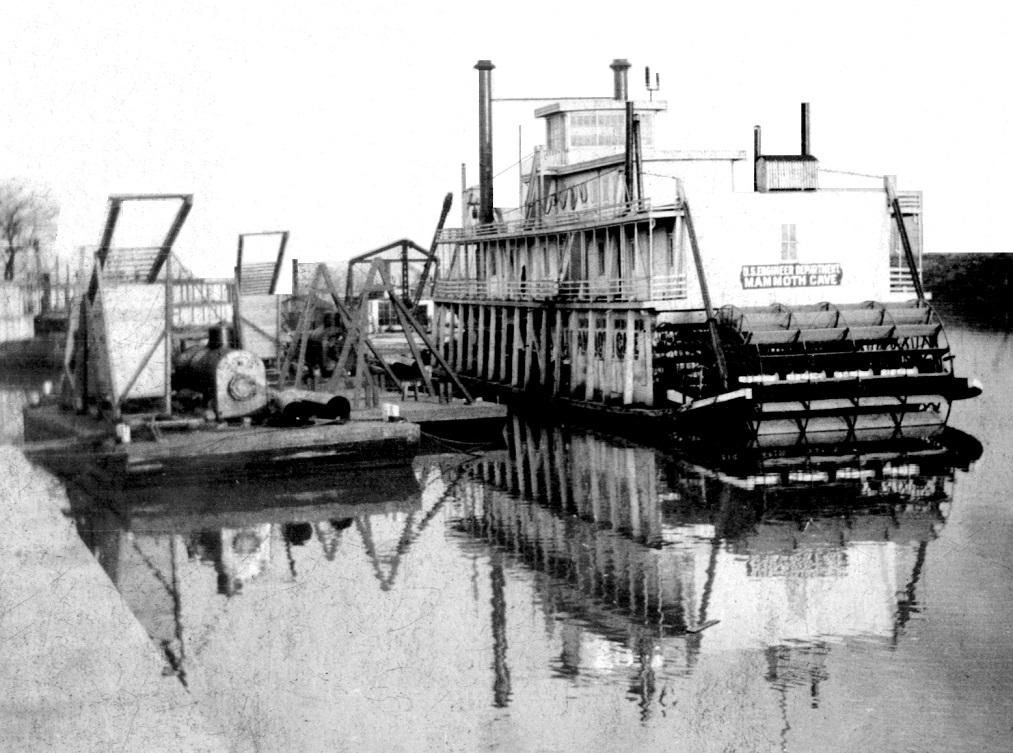

MAMMOTH CAVE Sternwheel Snagboat

Way's Steam Towboat Directory - T1708

Built in1908 at Jeffersonville, Indiana at Howard Ship Yard

U.S. Engineering Department; Tom A. and Jeff Williams

Captain William Drowning (master, 1920s)

Captain J.E. Wallace (master)

Captain B.O. Lerman (master)

Green River; Barren River; Tennessee River

Home port or owner's residence circa 1908, Louisville, Kentucky.

Original price: $30,830. Much of the equipment used in building the Mammoth Cave came from the WM. PRESTON DIXON.

Sold at a public sale on July 31, 1936 to Tom and Jeff Williams.

In November, 1936 Captain Hiernaux bought her, took her to Charleroi, Pennsylvania and rebuilt her into a towboat named RICHARD.

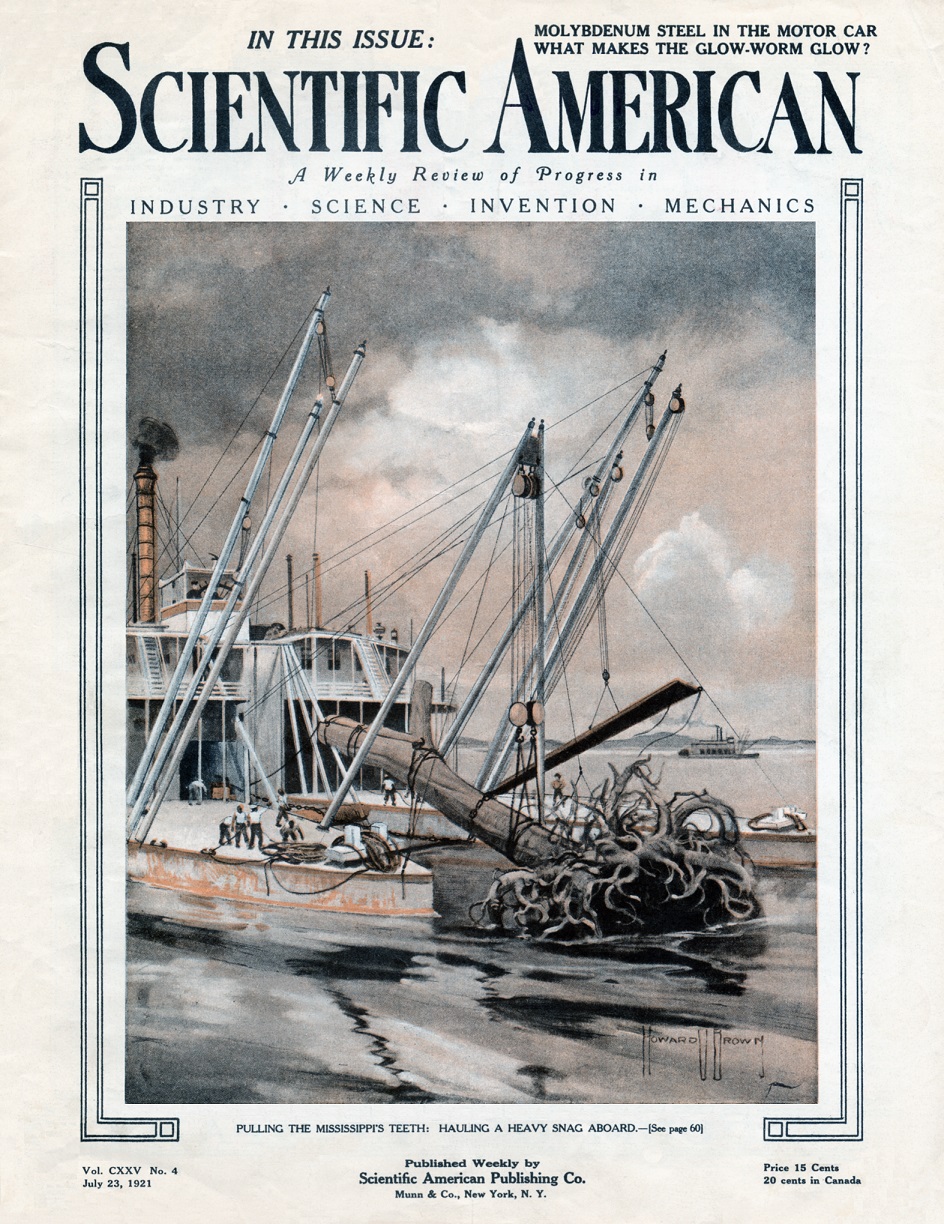

Snag Boat on the cover and story inside the 23 July 1921 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN magazine

SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

July 23, 1921

Cover art of a Snag boat by Howard V. Brown

Transcription of the story in that issue written by George H. Dacy that was printed on pages 60 and 70:

PULLING THE MISSISSIPPI's TEETH

What Is Being Done by Way of Making Our Longest River Navigable

Our Father of Waters, the peaceful, placid, tortuous Mississippi, which runs amuck and bursts its bounds only once in a dog's age, is unique as a channel of inland barter and commerce. Its shipping potentialities and prospects were long neglected during the period when rail traffic was in its 'teens. For this reason and that reason, because of disinterest of those who would be benefited most by its development or because Congress was always too busy with other affairs to bother much about the crooked, illy-navigable river, the Mississippi for scores of years pursued her catch-as-catch-can course, unharassed and unsung. River packets and freighters, scows and bumboats, dories and derelicts plied their difficult and hazardous ways between St. Louis and New Orleans. Year after year, the stationary volume of traffic and unchanging type of boat bore witness to our lack of appreciation of one of the best inland waterways with which any country ever was blessed. Participation in the international war changed the focus of the glass through which we had missed seeing the possibilities of the Mississippi River. The Mississippi at last came into her own and a belated development was instituted. Much has been done toward bettering shipping facilities and shipping conditions prospects are that much more will be done in the future.

The Father of Waters finally will occupy the prominent position in our interstate freight exchange which its natural advantages justify.

In January, 1918, the Director-General of the Railroads appointed a committee to study the possibilities of utilizing our inland, canal and coastwise waterways for transportation purposes. Six months later, an appropriation of approximately $8,000,000 was authorized by Uncle Sam for the construction of a federal fleet of barges to operate on the lower Mississippi. Twenty steel, flat-deck barges of the U. S. Engineers, capable of carrying 450 tons of freight apiece, as well as eight barges ranging in tonnage capacity from 400,E to 1000 tons, were immediately chartered for freighting service. Simultaneously, plans were devised and work begun on the construction of a fleet of new, auxiliary barges. These activities have continued even after the cessation of warfare with the result that right now the Federal barge line which operates out of St. Louis has in service six old-type tow-boats, one new self-type propeller tow-boat (5 similar boats are under construction) , 40 two-thousand-ton steel barges, and 4 smaller steel barges which range in size from 500 to 1000 tons.

With the remarkable improvement in the shipping facilities along the lower Mississippi,, the importance of maintaining the channel navigable and free of all obstructions has been intensified. This brings into the limelight the novel snag boats, the most extraordinary vessels which Uncle Sam supports—either in or outside of his Navy. The Mississippi carves out and carries away huge fragments of the banks that fringe her crooked course. Untold miles of these consist of farm timberlands and forests. As a result, she often dislodges and steals great strips of land containing large trees. These impediments she whips away only to have them sink and settle, ultimately, in the sand and mud of the open channel—there to effect evil and ruin unless discovered and eliminated by Uncle Sam's water sleuths. The general term "snag" may signify anything from a small tree of half a ton or so to an entanglement of large fellows weighing many tons. Whatever their size they must come out if they are in the channel.

Away back in the days of Mark Twain, Government snag boats were operated on the Mississippi, although the obstructions were not removed as scientifically and efficiently in that era as they are in the present. River-men and navigation experts say that this service will have to be continued as long as the river exists and is utilized for transportation purposes. The Government now maintains three large snag boats on the Mississippi, two on the lower river which police the beat that extends from St. Louis to New Orleans, and one on the upper river, north of St. Louis. One other large snag boat is operated on the Ohio River while smaller vessels patrol such tributaries as the Arkansas and Missouri.

For the last 33 years the Government has annually appropriated $100,000 for snag work on the lower Mississippi. Two snag boats, the "Horatio G. Wright" and the "John N. McComb" are specially designed and equipped for this service. The peak of their activities comes during the summer months from July on, when the river is low and the quest for snags is most fruitfully rewarded. The usual plan is to maintain one of these boats at the southern extremity of the Mississippi and the other in the northern districts adjacent to St. Louis, as bases. This means that the boats can speed to localities where snags are reported as dangerous in their respective zones without needless overlapping travel. In one trip of 1100 miles last summer, the "Horatio G. Wright" sighted, pulled and destroyed over 600 gigantic snags, the average weight being more than 40 tons while the heaviest topped 175 tons. The next trip over its beat, this police boat destroyed only 200 snags. River conditions, the water level, the season of year and various other factors influence the prevalence and appearance of snags, so that it is impossible to plan a definite and accurate campaign and to estimate the work and the number of snags which will be spotted and lifted in a certain season.

The maximum speed of the snag boats, each of which is about 190 feet long and 95 feet wide and carries a crew of 45 men, is approximately 83/4 miles an hour in still water. Ordinarily, the snags point down-stream and often are buried anywhere from 10 to 40 feet deep in the mud, the tendency for trees which are carried away in the shore-undermining activities of the turbulent waters being to right themselves and to settle in the sand in an erect, upstanding position. The snags are so securely anchored that they rip holes in the bottoms of vessels which collide with them. Waterlogged, anchored snags effect the greatest damage ; river pilots have had to contend with them ever since navigation between New Orleans and St. Louis was begun. The position of the snag in the water is indicated by the V-shaped break which it causes in the surface of the river. A snag submerged even as deep as 30 or 40 feet causes a boil in the overhead surface water which is easily recognizable by the lookouts on the snag boats. The Federal snag boats are of the double-bowed, catamaran type with a steel butting beam 15 feet long and 10 feet wide connecting the bows. When a snag is sighted, the boat is maneuvered close to the point where the V-shaped break appears on the water surface so that the crew can lower a huge sweep chain operated by means of 4 engine-driven capstans, each of which can exert a pull of 35 tons. The chain finally will engage the snag and raise its free end out of the water. Windlass chains are then used to haul the snag on to the beam, a special engine being used to run an enormous drum which releases or winds up a huge sansom chain that can resist a strain of 75 tons. The individual links in this chain weigh 27.5 pounds and are made out of round iron 23/4 inches in diameter.

In case difficulty is experienced in loosening the snag, the boat resorts to butting tactics. It backs away from the obstruction about 60 feet and then under full steam slides at the snag and smashes into it with its steel butting beam and 800 tons of total weight. This method of attack is repeated until the snag gives way. The shock of the concussion is so violent that frequently all the members of the crew are sprawled headlong on the deck and the fire doors under the boilers are knocked open. When the snag is freed sufficiently, the windlass chains are used to haul it up over the beam where it is placed in such a fashion that engine-driven saws may be used to cut the tree or obstruction up into sections about 20 to 25 feet long. These logs are then cast overboard and generally are salvaged and sold by squatters who live along the river banks or by parties in gasoline launches who follow the snag boats and make a business of gathering the drift logs and hauling them to sawmills and selling them. Sometimes, these loggers of the river realize $100 or $150 from a single day's work in salvaging stray logs which emanate from the activities of the Government snag boats. Snags which will not float after being dismembered are hauled on the snag boats to deep sections of the river and there dumped overboard. They sink in the sand and henceforward do no more damage.

Considerable danger is associated with the raising and destroying of the river snags, but despite the hazards, men like to work on the Government boats as there is a certain romance associated with this pioneering work which appeals to the adventurous natures of the rivermen. During the last score of years, four men have been killed and 60 injured on the snag boats as a result of slipping or breaking of chains or the sudden collapse of snags when they were pulled from their mud beds. In the case of wrecks which have sunk to the bottom and are dangerous to traffic, experienced divers are employed to salvage the valuable machinery and then the heavy drag chain is used to smash them into small timber. Sometimes accidents ensue here.

These unusual craft of Uncle Sam are also employed in raising wrecks which are still serviceable. A noteworthy accomplishment of this description was the lifting of the wrecked packet steamer "John Simonds," sunk during the Civil War and raised to the surface a half century later. The machinery in this boat was still in excellent condition despite its long sojourn in the water.

The wood work of the boat was also well preserved. The water does not seriously injure the metal or wooden parts of a sunk ship it is the mud which effects the bulk of the damage. Wrecks which are not imbedded in the mud and sand survive decomposition for many years. During the periods When snag work on the river is not pressing, the snag boats occasionally assist private companies in the raising of river boats which have been sunk at sections of the river adjacent to the open channel. Such assistance is furnished at actual cost.

Despite the great increase in labor costs, Congress appropriates the same amount for snag removal from the Mississippi today as 30 years ago. The consequences are that the two snag boats which are supposed to patrol the river from St. Louis to New Orleans are not able to work a full season—the snagging season usually lasts from July until March. Lack of funds is halting this essential work just at a time when the Mississippi River is being used more than ever before. It is now highly necessary to keep the channel clear and navigable and to do everything possible to promote the increased utilization of this wonderful inland waterway. It would seem that Congress might allot a few thousand dollars more a year to this meritorious cause.

Just to show that the money used in the past has been effectively expended, it may be cited that during a normal season, the two Government snag boats on the lower Mississippi will pull and destroy between 300 and 400 snags, the average weight of these obstacles being between 30 and 40 tons. In addition, they will break up anywhere from 10 to 20 drift heaps which—if neglected—are inimical to navigation. The crews of the two boats in addition will cut between 200 and 10,000 trees which fringe the banks and are liable to be undermined and washed away by the river and ultimately converted into dangerous snags. The conquest against snags in the open channel is well in hand, at this time, and with sufficient funds to continue the work it -will be possible to keep the number of accidents due to snags down to a minimum. However, to neglect the work at this stage of the game due to lack of funds is a costly, senseless and unnecessary error. The American public desires that Congress reduce expenses along sane and sensible lines. It does not wish our legislators to rob Peter to pay Paul in the style evidenced by the 1921 lack of adequate appropriation for the complete and efficient removal of snags from the Mississippi.

COVER ART by Howard V. Brown, Artist of Technical Subjects

Special thanks to Steve Kirch for help in researching this artist's note.

magazineart.org

Anyone looking at the covers of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, RADIO NEWS, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, EVERYDAY ENGINEERING, or ASTOUNDING SCIENCE FICTION in the early years of the twentieth century would find a familiar style and an unmistakeable signature. Howard V. Brown probably had as much to do with shaping our concept of the future as any three science or science-fiction writers you could name. What the futurists thought, Howard put into pictures so we could immediately see what it would be like.

There's a listing of his cover art for the SF magazines at the ISFDB site, which gives his birth and death dates as:

Birthdate: 5 July 1878 / Deathdate: 1945. Detail on Brown seems to be in short supply.

There is a short, incomplete bio of Brown floating around with internet, with some obvious errors and without attribution:

"Howard Vachel Brown was born in Lexington, Kentucky, and received his art education at the Chicago Art Institute. His work was exhibited at the National Academy and featured by the the International Exhibition of American Illustrators. From 1913-1931 Brown was the cover illustrator for Scientific American. He also illustrated for Gernsback's Electrical Experimenter, 1916-1917, and Argosy and Science and Invention in 1919.

Brown created every cover from January 1934 through May 1937 of Tremain's Astounding Stories and did about half of the covers through November 1938. After Gernsback lost Wonder Stories and his main artist Frank R. Paul stopped doing covers for that magazine, Brown did every cover from August 1936 through August 1940, with the exception of the August 1937 issue, which was done by H. W. Wesso.

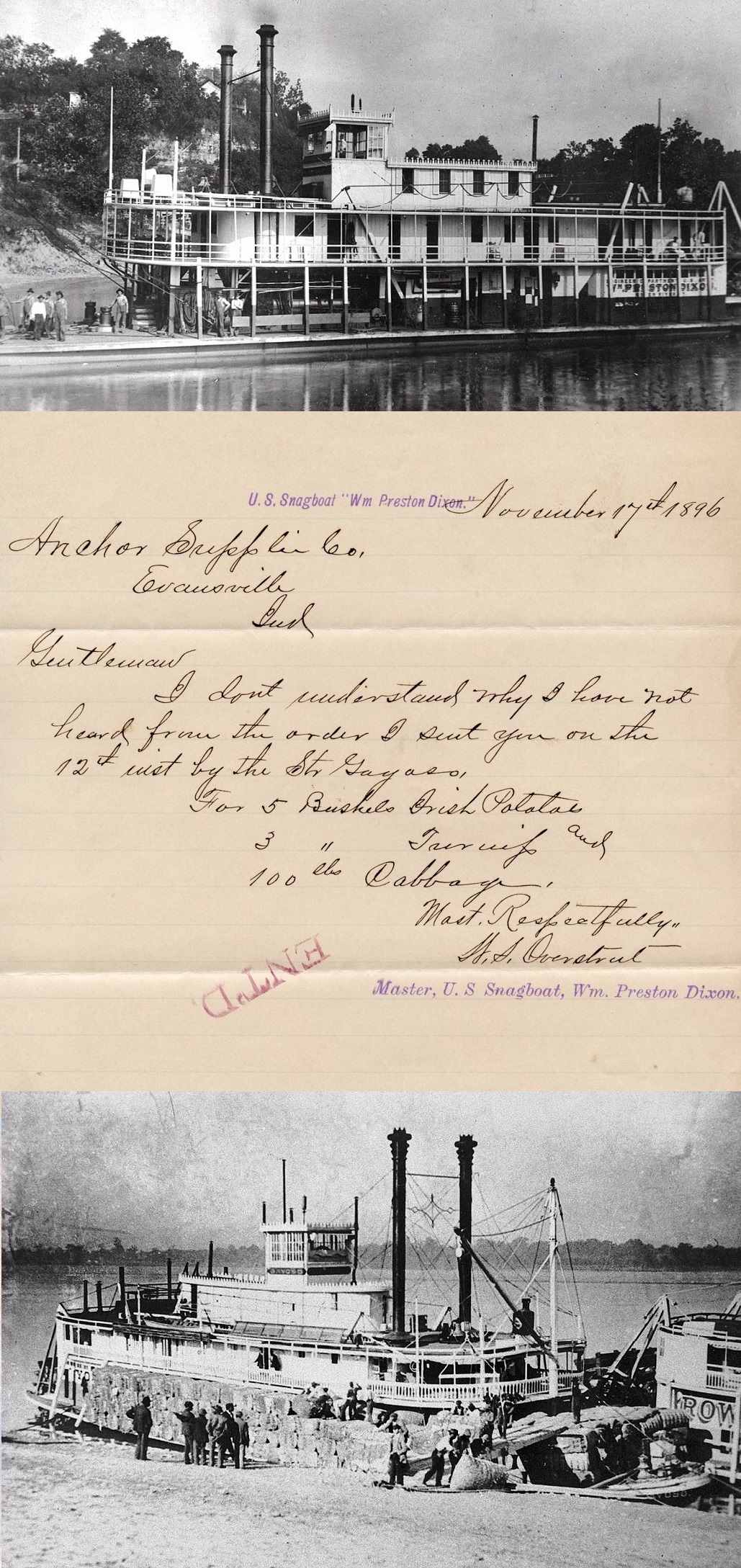

Letter from Snagboat Wm. Preston Dixon requesting supplies

Have acquired 3 letters from the Master of the Snagboat WILLIAM PRESTON DIXON, all written in November 1896

Attached is a scan of the 3rd and last letter dated November 17th from Capt. Overstreet to the Anchor Supply Co. of Evansville, Indiana (on the Ohio River) asking why his order by a 2nd letter had not been filled yet. His 1st letter dated November 7th to Anchor Supply listed what he wanted with a request to let him know how much they would cost and that he would want them to be delivered to him on the Green River.

Overstreet's first letter was returned to him with prices written on it pencil by Anchor Supply. In his second letter he confirmed his order. The Captain mentions that the correspondence was transported to Evansville by the cotton packet GAYOSO. We don't know if the Irish potatoes, turnips and cabbages were finally delivered to the DIXON or not.

Above the letter from November 17th I have included a photo of the DIXON and below the letter a photo of the GAYOSO. Both photos are from the La Crosse collection.

Here is a transcript of the hand-written letter:

[From]

U.S. Snagboat "Wm Preston Dixon."

November 17th 1896

[To]

Anchor Supply Co.

Evansville, Indiana

Gentlemen

I don't understand why I have not heard from the order I sent you on the 12th last by the Str Gayoso,

For 5 Bushels Irish Potatoes

3 Bushels Turnips and

100 pounds Cabbages.

Most Respectfully,

H.S. Overstreet

Master, U.S. Snagboat Wm. Preston Dixon.

WM. PRESTON DIXON

Sternwheel Snagboat/Towboat

1890-1908

Way's Steam Towboat Directory Number T2679

Built by James W. and M.A. Sweeney in 1890 at Jeffersonville, Indiana.

Operated by the U.S. Corps of Engineers on the Green River in Kentucky.

Captain B.O. Lerman (master); Captain Raleigh Bishop (master)

In 1908 she was replaced by the Snagboat/Towboat MAMMOTH CAVE.

GAYOSO (Packet, 1883-1897)

Sternwheel Cotton Packet

Way's Packet Directory Number 2210

Built in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, at Axton yard, 1883

Cotton packet; ran Memphis-St. Francis River, owned by the Lee Line, Memphis.

Sold to Captain Elmore Bewley in January 1895 for the Evansville-Green River trade.

The name was changed to PARK CITY in November 1897

In the David L. Rice Library at the University of Southern Indiana there is a photo of Anchor Supply taken during the Ohio River flood of 1937 http://library2.usi.edu:8080/cdm/ref/collection/1937_Flood/id/1876

Anchor Supply Co. at 121-25 NW Riverside Dr., on the corner of Vine St.

Handles on that pilot wheel are awful chubby, hard to get a little "mitt" around one. Traveler's insurance ad from inside pilot house with snag boat in distance on the river.

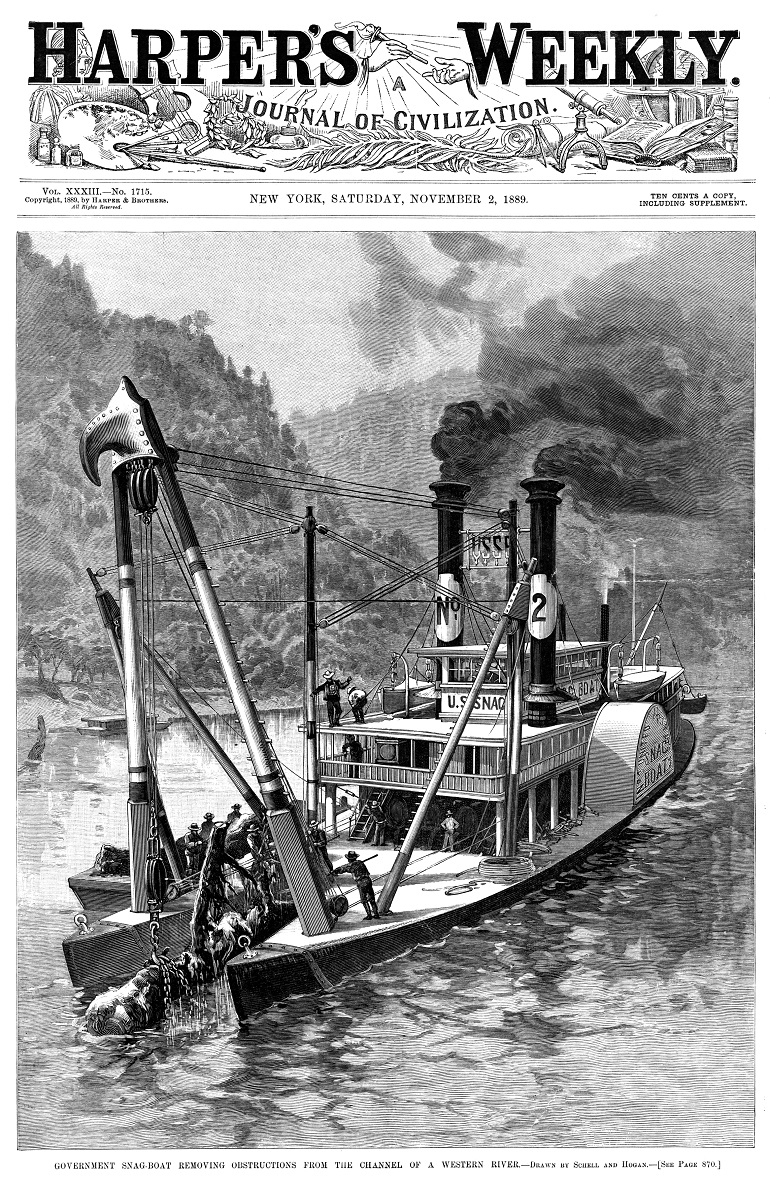

"One of Uncle Sam's Tooth Pullers"

The snag boats operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers were sometimes called "Uncle Sam's Tooth Pullers," referring to how the vessels extracted whole trees and logs that hindered navigation. U.S. Snag Boat No. 2 is shown pulling stumps from the river bottom.

From Harper's Weekly, Nov. 2, 1889 amhistory.si.edu

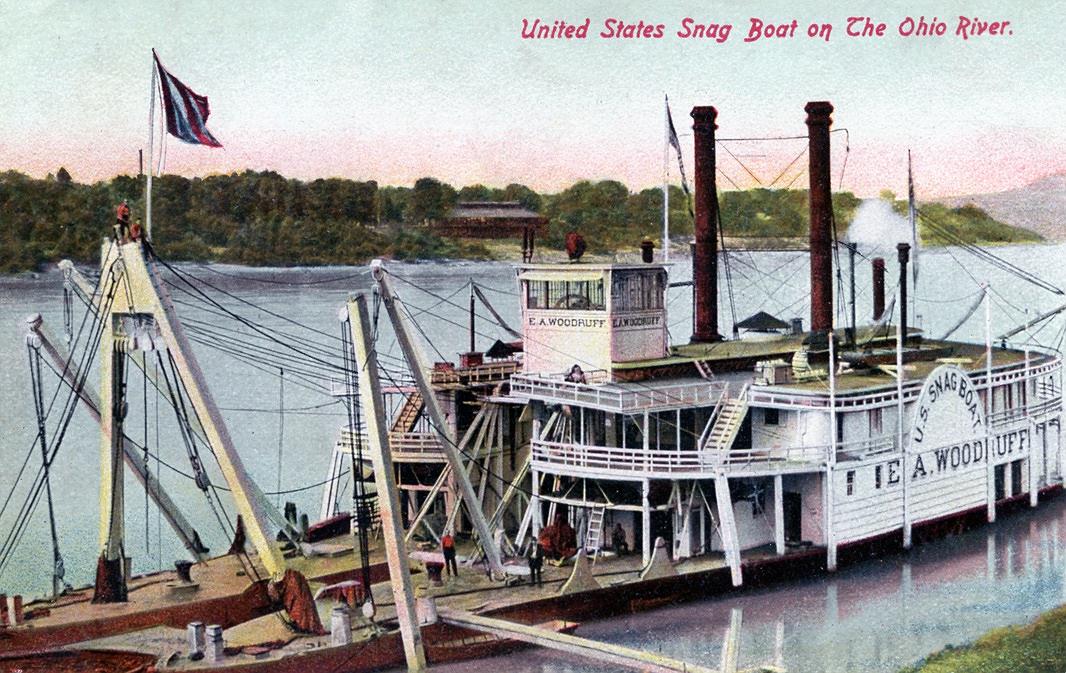

Pictorial postcard post marked 7th May, 1908

E.A. WOODRUFF

1874-1925

Sidewheel Snagboat

Way's Steam Towboat Directory Number T0649

Built in 1874 at Covington, Kentucky (hull) and completed at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Covington Iron Works built the hull and the machinery was installed by Hartupee. Owned by U.S. Engineering Department

The hull was shaped like a bootjack with a "Shreve snag beam" between the double bows at the waterline. Lengthened at the Cincinnati Marine Ways in 1885. Operated the entire length of the Ohio River. Captain Christian commanded her for about 25 years. One of her early jobs was to remove the wreck of the sidewheeler PAT CLEBURNE in November 1876. When she was retired in 1925, Captain Gordon C. Greene was high bidder on her. After Greene died in 1927, she was sold to the Louisville and Cincinnati Packet Company and became a wharfboat at Louisville, Kentucky. In 1940 the Greene Line, then owners, built a new wharfboat and the remains of the WOODRUFF were sold to the Ohio River Company, who beached her at Catlettsburg, Kentucky where she was dismantled.

U.S. Snagboat Montgomery

Press release photo from the Mobile Press Register dated 3 April, 1961

From U.S. Corps of Engineers MOBILE DISTRICT website:

U.S. Snagboat Montgomery A NATIONAL LANDMARK

usace.army.mil

The Department of the Interior designated the U.S. Snagboat Montgomery a National Historic Landmark in June of 1989. Serving as one of the last steam-powered sternwheelers to ply the inland waterways of the South, the Montgomery's impressive history involved seven of the South's navigable rivers. Beginning on the Coosa and the Alabama rivers from 1926 to 1933, crews used her derrick and grapple to remove snags and debris from the river channels. In 1933, she was transferred to the Black Warrior and Tombigbee rivers. Her final work stations were the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee, and Flint rivers in Florida, Alabama, and Georgia, where she served until her retirement in 1982.

The Montgomery was one of the hardest-working snagboats in the Southeast. She was commissioned by the Montgomery District COE and built in 1926 by the Charleston Dry Dock and Machine Company of Charleston, South Carolina. The boat was based in Montgomery until 1933, when the Montgomery District became part of the Mobile District, and the boat was moved to her new home port of Tuscaloosa. However, she continued to work the waters of the Coosa River system, adding the Black Warrior-Tombigbee Rivers to her responsibilities. The Montgomery pulled snags from these river systems until 1959, when she was transferred to Panama City, Florida. She worked on the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee, and Flint rivers from 1959 for the rest of her career, though her home port was transferred from Panama City to White City, Florida in 1979.

The Montgomery is a riveted steel sternwheel-propelled vessel with a steel hull and wood superstructure. The overall length, including the sternwheel, is approximately 54 meters (178 feet), while the maximum width is approximately 10 meters (34 feet). The depth of the hold is 1.8 meters (6 feet). The Montgomery has three decks. The propelling and snagging machinery, crew quarters, and the engine room are located on the main deck. The second deck contains the galley, officers' quarters, and an office; and the pilothouse at the top of the boat contains controls for the snagging boom and engine room. The boom is operated by two large steam winches; one turns the boom in an arc in front of the boat while the other lifts the snag. The Montgomery still has its original Scotch boiler, which created steam to power the boat. Water was heated inside a cylinder within the boiler. The steam produced by the boiler was extracted from the top of the boiler and passed through the main steam line overhead to the engine room in the stern. The boiler originally burned coal, but was converted to burn fuel after World War II. The engines are high-pressure, or non-condensing, joy valve engines; and the paddlewheel is constructed of steel and wood and is 5.5 meters (18 feet) in diameter and 6 meters (20 feet) long. One interesting feature of the Montgomery is the telegraph machine located in the engine room. The machine has a dial with a hand that points to different possible engine room actions and is the way the pilot originally communicated with the engineers; a similar telegraph is located in the pilot house.

In early November 1964, the Montgomery assisted in raising the remaining section of the Confederate Gunboat Chattahoochee from the channel of the Chattahoochee River. The activities are recorded in the Master Fleming's daily log: "Picking up stern section of Gunboat and Removing it from channel. While picking up Gunboat and trying to work it on the bank some of the upper sections of the boom were sprung." Today the Confederate Gunboat Chattahoochee can be seen at the Port Columbus National Civil War Naval Museum in Columbus, Georgia.

Steam-powered boats, like the Montgomery, dominated transportation and commerce for most of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; however, river transportation began experiencing competition from railroads as early as the mid-nineteenth century. The continuing explosion of transportation technology in the twentieth century, including interstate highways, automobiles, trucks, and airplanes, eventually spelled the end of steam-powered boats. When the Corps of Engineers retired the Montgomery on 8 November 1982, she was one of only two snagboats remaining in the United States. On her final day of service, the Captain wrote of the Montgomery in his log: "Me and [the crew] are very sad this day!! This boat has been a workhorse of the tri-rivers."

In 1984, the Mobile District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers awarded a contract for extensive restoration work on the Montgomery. This work included replacing old material with new, sandblasting the entire hull and coating it with five layers of paint, and draining and cleaning the diesel fuel bunkers. After her first restoration, the Montgomery was moored at the Tom Bevill Visitor Center, Pickensville, Alabama. Visitors could tour the boat, reliving her days on the South's rivers.

The Montgomery has another claim to fame. In 1984, the Montgomery was used as a set in the television movie Louisiana, which starred Margot Kidder, Ian Charleson, Victor Lanoux, and Andréa Ferréol. In the movie, the Montgomery is repainted and modified to resemble an ante-bellum passenger sternwheeler. However, the Montgomery has an unfortunate end in the movie; during a riverboat race, the sternwheeler explodes.

Beginning in the early 21st century, the Mobile District realized that exposure to river traffic and environmental factors were causing irreparable harm to this National Historic Landmark. They made the decision to remove her from the Tennessee - Tombigbee Waterway. On 2 October 2003, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mobile District, with the assistance of two derrick barges lifted the Montgomery on a specially-designed cradle and placed her in a dry mooring basin beside the lovely Tom Bevill Visitor Center.

In late 2003, a maintenance plan was developed for restoration of the Montgomery. In early 2004, extensive restoration began. Contractors under the direction of USACE's Tennessee-Tombigbee Regional office, removed and replaced rotting decking, painted all exterior and interior surfaces, and replaced the pilot house windows and framing, along with numerous other tasks.

The History Workshop, a division of Brockington and Associates, Inc., developed a new interpretive plan that includes this website, new interpretive panels on the boat and the surrounding walkway, educational materials, a touch screen kiosk, video presentations, and two brochures.

All of this work culminated with a Grand Re-Opening and Restoration Celebration on 28 October 2004. After an early morning tour of the restored boat, Former Master Cleve Fleming cut the ribbon reopening the Montgomery to the public. That afternoon, sixth graders from Pickens County were among the first to tour this restored sternwheeler. Today, the U.S. Snagboat Montgomery, a National Historic Landmark, is one of two remaining steam-powered sternwheel snagboats in the United States. Please come to Pickensville and see her for yourself.

With the exception of images credited to public institutions,

everything on this page is from a private collection.

Please contact Steamboats.com for permission for commercial use.*

All captions provided by Dave Thomson, Steamboats.com primary contributor and historian.