New Items - Ephemera, page 3

Steamboat Cyclone

Capstan from the CYCLONE

Manufactured by American Ship Windlass Co.

Providence, Rhode Island in 1890

Salvaged after the 1907 fire that Destroyed the CYCLONE and preserved near the Mississippi River in Wabasha, Minnesota

Photos by Dave Thomson taken in 1991

CYCLONE

Way's Packet Directory Number 1399

Sternwheeler built at Stillwater, Minnesota in 1891

121 X 22.6 X 4

Engines 14's - 5 feet

Ran Wabasha - St. Paul 1900 - 1907

Captain Milt Newcomb.

Burned on the ways at Wabasha, Dec 2nd 1907.

Illustrated Glossary of Ship and Boat Terms

J. Richard Steffy

The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology

Edited by Ben Ford, Donny L. Hamilton, and Alexis Catsambis

Print Publication Dec 2013

Capstan:

A spool-shaped vertical cylinder, mounted on a spindle and bearing, turned by means of levers or bars; used for moving heavy loads, such as hoisting anchors, lifting yards, or careening vessels.

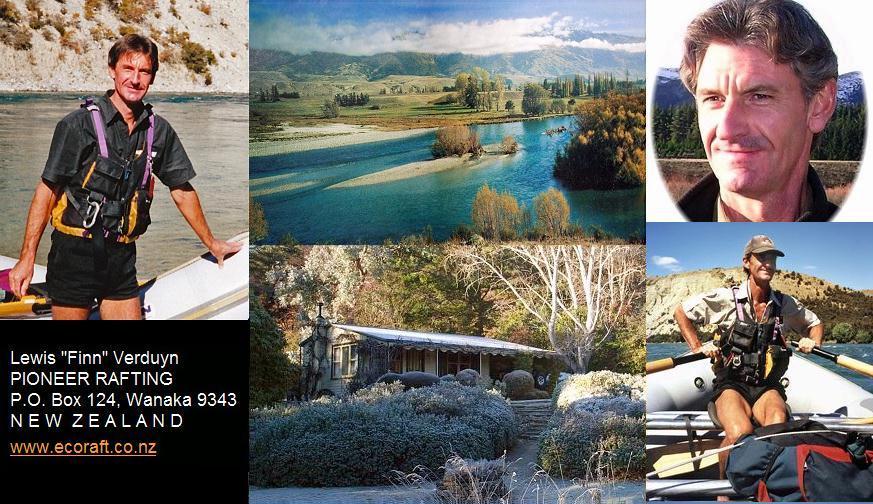

Page dedicated to Lewis Verduyn CLUTHA RIVER in New Zealand Geographic 2003

Steamboat Times. A History of Navigation on the Mississippi River System

Created and maintained by Lewis Verduyn

Copyright 2007

Key words: Steamboat, Sidewheeler, Sternwheeler, Packet Boat, Riverboat, Mississippi River, Missouri River, Flatboat, Mackinaw, Keelboat, Raft, Fur Trade, Santa Fe Trail, Mark Twain, Huck Finn, Tom Sawyer, Hannibal, St. Louis, Cairo & New Orleans.

Distribution: Global

I was shocked and deeply saddened to discover that Lewis Verduyn passed on at age 60 on the 21st of August 2019.

steamboattimes.com

Lewis was a wonderful correspondent and his e-mails were always full of tales of his life, times and many adventures as a river rafter and conservationist. I will miss him and wish that we had met in person.

Message from Lewis 23rd December 2018:

Hello Dave,

It's one of those clear sky and calm mornings here, and I sure hope we get a breeze later, otherwise it will be mighty hot. Tomorrow, Christmas day, the temperature is supposed to be 31Celsius (equivalent to about 88 degrees Fahrenheit) but unofficially, down the river valley, it is usually several degrees hotter. I must get outside before it heats up. When the days are like this, I like to pump my water from the river into my tank in the mornings (using my old circa 1930s electric windmill water-pump), and I also like to check my plantings including my vegetable garden.

I hope all is well with you, and that you have a very pleasant and peaceful Christmas and New Year.

Your friend on the riverbank,

Lewis.

OBITUARY

Lewis VERDUYN

Published in Southland Times from Aug. 21 to Aug. 24, 2019

Sadly Lewis passed away at his home in Luggate; aged 60 years. Much loved youngest son of Catherine and the late Jacob, loved brother of the late Roger, a much loved nephew, uncle, and cousin of all his family in New Zealand and Holland. In accordance with family's wishes a private cremation has been held.

Memorial service for Lewis Verduyn was held at 2.00 pm Saturday 5th of October 2019

The Red Bridge River Park Trust invited friends of Lewis to a memorial service for him at Reko's Point on the Clutha River on Saturday 5 October at 2 pm.

The memorial paid tribute to the life of a friend, teacher and visionary. Lewis' ashes were scattered at the river and there was an opportunity for those who knew him to say some words. Attendees were invited to bring with them a cup for Manuka Tea.

NEW ZEALAND GEOGRAPHIC

ISSUE 065

SEP - OCT 2003

nzgeo.com/stories

WHAT PRICE A RIVER?

WRITTEN BY DEREK GRZELEWSKI

Drawing on a vast catchment in the mountains west of Lakes Wanaka and Hawea, the Clutha River—New Zealand's largest by volume flows through the parched country of Central Otago before pouring into the Pacific Ocean. It delivers precious irrigation water to the region's burgeoning horticultural enterprises and turns the turbines of two of the nation's largest power stations. But problems with sedimentation in the hydro lakes and a boom in property development along the Clutha's banks are beginning to threaten the river's integrity.

Lewis Verduyn had a dream: a hankering to step back in time. He had in mind a voyage by log raft in the wake of the pioneer timber rafters of the Clutha River. His inspiration lay in the 1860s, when a small group of timbermen with a penchant for mixing business and adventure established a profitable but highly dangerous delivery route from the forests of today's Mount Aspiring National Park to the treeless and timber-hungry settlements of Central Otago. The link between the two areas was the Clutha, the largest river by volume in the country.

Because the Clutha is only sporadically buckled by rapids and hairpin bends, the men saw it as a reliable, high-speed conveyor belt. They would buy logs from sawmills on the Matukituki and Makarora Rivers, lash them together into rafts, then pole their unwieldy craft into Lake Wanaka. There they would combine the rafts into large floating islands of timber, rig them up with square sails and, helped by the prevailing north-westerly winds, row their way across the lake to the source of the Clutha River.

It was here, at the point where the lake funnels into a single powerful waterway, that the conveyor belt began. The men would split their timber islands back into smaller log rafts, outfit these with rowlocks and eight-meter sweeps and push off into the current.

From its outset, the Clutha flows so fast that the men could make their 80 km journey in a single day. They had to be wary of major rapids such as at Devils Nook, a notorious dog-leg bend, and the Boiling Pot, where the current warps on entering Maori Gorge. The river could smash a raft like a matchstick toy at these places, and the men often preferred to walk the banks and ease the rafts on hemp ropes down the most difficult stretches.

Landing near Cromwell, they would dismantle their craft and pile up the timber for sale. After an overnight stay at the local hotel, they would head back to Wanaka on foot, carrying their ropes with them. That same afternoon they would construct another set of rafts from the logs that awaited them at the outlet, to be ready to push off the following dawn. Three Clutha trips a week could be made, and although several men lost their lives to the river, the financial returns were considered worth the risks.

"It was strenuous work," wrote one of those good keen men, named George Hassing, "but we were young . . . and delighted in it."

Lewis Verduyn was young, too, and an experienced rafting operator to boot. His plan was simple: build a log raft, retrace the timber route and then extend the voyage all the way to the sea. He wanted to taste the hardships and relive the perils of the pioneers. The river would not disappoint him.

His first five-ton Oregon-pine raft, named DESTINY was swept away by a flash flood only two days into the trip and was never seen again. Lewis was undeterred. He built a second raft—seven logs and four braces tied together with 200 metres of natural-fibre rope—which he poled and sailed from Makarora to Wanaka. Then, after some dry-dock repairs and strengthening, he navigated DESTINY II out of the lake and into the Clutha.

Over the following days he and his crew poled, pulled, pushed and steered the lumbering eight-by-three-meter craft around innumerable obstacles on their journey to the sea. Sometimes they simply hung on for dear life as the river gave the four-and-a-half-ton plaything a bucking-bronco ride.

The raft was repeatedly stranded on shoals and snagged by sunken trees, called "strainers" in white-water parlance. It capsized more than once, to be righted by skillful maneuvering into the rocks and current, or with the help of local farmers, using horses or tractor. It was lifted by crane over the Roxburgh dam (the Clyde dam had not yet been built), and turned into a submarine after hitting a giant "stopper" wave in the Cromwell Gap, when the river closed over Lewis, spread-eagled on the deck, for what seemed like a breathless eternity.

Finally, 440 km and 15 river days after leaving Makarora, Lewis nursed his battered raft into the Pacific Ocean for a beach landing. He had fulfilled his dream, and in the process come to know the river intimately. An unusual bond had formed between man and waterway, as if the Clutha's muscular flow now coursed through Lewis's own bloodstream. Although the voyage took place 20 years ago, in the summer of 1981 - 2, Lewis has lived to the rhythms of the river ever since.

When I first met Lewis in his riverside cottage—fittingly, the former residence of a ferryman—we talked river for hours, two enthusiasts applauding the nuances of an endless performance. Like the pioneers he emulated, Lewis has combined adventure and business in a river-based lifestyle: an eco-rafting venture focusing not just on white-water thrills but appreciation of the riverine environment as well. It was late April when we met, and he had just completed his 21st rafting season. This called for a celebration, he thought: one last trip of personal thanksgiving to the river for a season of plenty. He invited me to join him.

The Clutha's quiet but formidable power comes from its large catchment area. Figuratively speaking, the river is like the trunk of a giant tree, with a deep and complex root system. Three large lakes—Wanaka, Hawea and Wakatipu—anchor the system in the foothills of the Southern Alps, but the tributaries which feed them penetrate beyond the Southern Lakes district into Fiordland and as far north as Haast. The Greenstone, Caples, Rees, Dart and Route Burn; the Wilkin, Young, Makarora, Matukituki and Hunter—all these rivers form the headwaters of the Clutha, whose total catchment extends over some 20,582 square kilometres. At 322 km from source to ocean, the Clutha is not a particularly long river, but it more than makes up for shortness with volume, speed and power.

These attributes are apparent as soon as we launch Lewis's inflatable raft at Albert Town, near the first bridge that spans the river. It picks up speed instantly, moving at 15 - 18 km/h, Lewis estimates, without a single oar-stroke. The water is as clear as kirsch: I can see the rocks of the riverbed three or four meters below us rushing past like a landscape through the window of a train.

Water clarity is one of the Clutha's outstanding features, Lewis tells me. It is the result of the decanting effect of Lake Wanaka. "The lake acts as a sediment pond for the glacial silt, and then the top layer of spring-pure water is drained off by the river," he says. "You can safely drink it . . ." He hesitates. "Well, at least as far as the Wanaka sewage outlet."

On this April day the autumn colors are in full blaze, and the Clutha is a plait of greenstone set in gold, the riverside poplars burning bright like rows of candle flames. The raft's paddles, I note, are stowed away, and Lewis, seated on an elevated center frame, is using a pair of oars instead. The frame, made of bull-bar-like aluminum tubing, is rounded so as not to catch on rocks or branches. Beneath it, the raft's hull is pliable, able to pour like water over the surface of obstacles.

Oar rafts are rare in New Zealand, Lewis says, but they are standard on big overseas rivers such as the Zambezi and Colorado. "You could never get away with a paddle raft on a river like the Clutha unless you had a coordinated and responsive crew, and you can't expect novices and tourists to become experts within minutes of putting in," he tells me. "I encourage them to paddle so that they can feel the strength of the current, but I retain full control over the raft. On the Clutha, you can't afford mistakes."

Most of his passengers assume that because the Clutha has no big rapids there is no danger, Lewis says. "They don't realize that it is the flow of the river and not its white water that is the greatest threat. So they enjoy the cruise and the scenery, unaware that if I were to misjudge a turn we could all be swimming within seconds, perhaps dead within minutes."

Tanned and toned, wearing his usual shorts and rafting sandals despite the morning's frost, Lewis works the oars with measured crank-handle spins, pirouetting the raft casually, aligning it with the flow, making the most of the current's intricacies. He cranes his neck to scout the route ahead, but his actions are relaxed and understated, testimony to more than two decades on the river.

Only when he allows me a turn at the oars on the Pioneer Rapid—the biggest stretch of white water on this part of the river—do I gain a proper insight into his skills. We plunge into a set of standing waves that come at us like an express train. I fend them off, straining to keep the raft on course. The river yanks and wrings the oars, then jabs them into my ribs, almost knocking me off the seat. It's as if we're in a scene from Deliverance, but Lewis is sitting back, a relaxed passenger. He knows he is not taking any chances. The rapid may be boisterous and look threatening, but it's also wide and devoid of obstacles. We could probably get through it without any oar work at all.

Lewis takes over just before Devils Nook—certainly not a place for a rookie oarsman. Here the river narrows, speeds up, then hits a cliff head-on, folding back on itself and creating a whirlpool 50 meters across—a giant no-escape eddy. Imagine a satellite image of a tornado and translate it to the aquatic realm: a twister of such power it makes the water look as thick as ready-to-pour concrete. It is enough to curdle the blood, too, but Lewis maintains his dance-with-the-river equanimity.

He plays the whirlpool so that the raft spirals in its grip, now rushing at the menacing cliff, now coursing back upstream. There are baby twisters calving off this mother of all whirlpools, and Lewis is craning his neck again, looking for an opportunity. Suddenly, he digs in the oars, locking into a breakaway vortex just as a surfer would catch a wave, and we are pulled out of the trap, spiraling into the mainstream. Below us, the Clutha again flows as smooth as silk.

Lewis Verduyn has learnt first-hand about both the river's power and its benevolence. Once, out for a summer swim, he was caught in an eddy and sucked beneath the surface. Twice he came up, grabbed a lungful of air and swam for his life, but both times the eddy pulled him back down. Third time around, Lewis blacked out. When he regained consciousness, his knees were scraping the shingle below the bank. Miraculously, the river had let him go.

"I learnt a big lesson that day," Lewis told me. "The moment before I blacked out I turned towards the middle of the river and let the current take me. That probably saved my life. The lesson was: don't fight the river—it is always stronger. But with skill, understanding and a good dose of respect you can use the river's power."

These days Lewis Verduyn has another dream—no less challenging than his log-rafting trip but far grander in scope. It is a dream of giving back to the river, of reciprocating its many blessings. Inspired by a scheme developed for the Mississippi, Lewis has proposed the Clutha River Parkway, a protected area encompassing the river and its banks from source to sea.

The parkway would incorporate existing reserves and seek the support of landowners and community and interest groups to regulate further development adjacent to the river. It could ultimately lead to the creation of a riverside trail, to be travelled on foot, mountain bike or horseback.

It is an appealing and unifying vision—and timely, in view of the wrangling over water rights. I can think of no better honor for my home river.

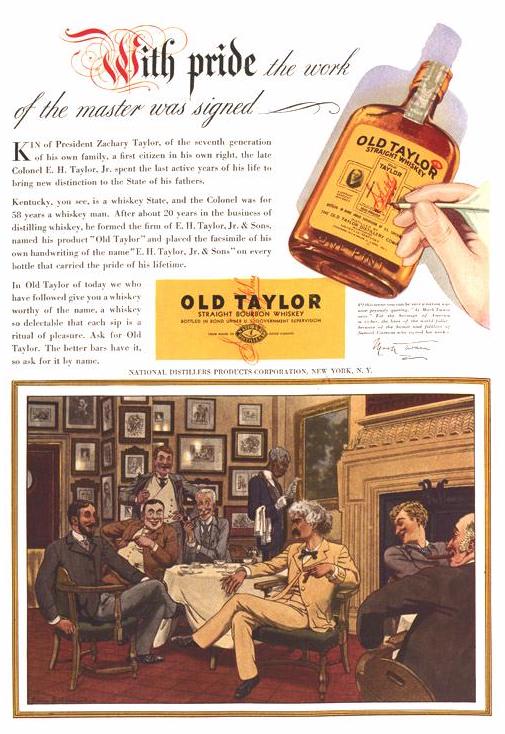

This scene of Mark Twain at the Lotos Club was used in an ad for Old Taylor Kentucky Whiskey.

Pierre Brissaud. Illustration of Mark Twain at the Lotos Club.

FROM CORNELL UNIVERSITY'S SITE "THE BUSINESS OF BEING MARK TWAIN."

Pierre Brissaud.

Illustration of Mark Twain at the Lotos Club.

From an advertisement in Country Life, February 1937.:

Pierre Brissaud was a French Art Deco illustrator, painter and engraver. His illustrations of the well-to-do appeared in French and American magazines and books.

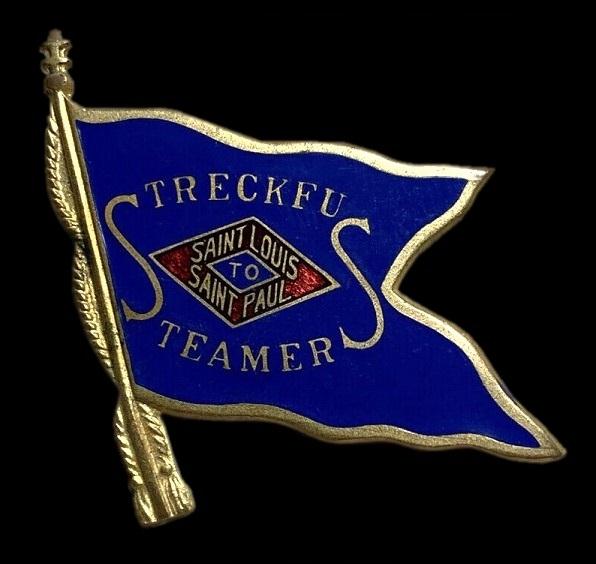

Streckfus in my nautical cap

Attached the Streckfus Steamers pin that my favorite eBay dealer listed among his other steamboat ephemera for my benefit.

I attached the to one of my favorite nautical caps where it looks right at home. I sent you a file previously of the pin by itself over a different sort of background but this version over black is even more striking.

Streckfus steamers and the family that ran them with photos and advertising will make a great page. You can bring in brochure covers and items from other pages that promoted cruises and there's also a photo that I took of young Verne Streckfus in the pilot house of the modern NATCHEZ at New Orleans that should be included.

A page devoted to Cotton Packets is something we need. These steamboats are easy to spot among out photos and engravings because they are stacked high with cotton bales. Cooley's AMERICA was a cotton packet and we have some images of the boat with a heavy cargo of bales and there's a painting of it that Ray Samuel of New Orleans had in his magnificent home in the Garden District where I photographed him.

Steamboat War Eagle baggage tag

LA CROSSE COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

La Crosse County Historical Society discovers, collects, preserves, and shares the history of La Crosse County, Wisconsin.

Steamboat War Eagle baggage tag

This article was originally published in the La Crosse Tribune on April 22, 2017.

https://www.lchshistory.org/things-that-matter-2017/2017/5/9/rlmp123ks1lf1vuiirxiujcw1q5wl1

By Robert Mullen

Catalog Number: 1947.001.07

Somewhere, somebody has a claim to some very old luggage sitting at the bottom of the Black River at La Crosse. All they need to prove their ownership is to produce a baggage slip from the steamer War Eagle, dated May 14, 1870, for item No. 10.

That date was the evening that the Steamboat War Eagle burned and sank at the riverbank just north of today's Riverside Park. Along with the boat, the fiery disaster destroyed the docks, the Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad depot, several freight warehouses and grain elevators, and a passenger train nearby. At least five people died.

In addition, most of the personal effects of the approximately 40 passengers were left behind during the frenzied escape from the burning boat. The staterooms on steamboats were small, so most belongings had been checked and stored in baggage compartments. Oscar Topliff, the vessel's assistant baggage manager, saved some luggage under his care that night, but not that of at least one unlucky passenger.

This brass tag was strapped to that property. Stamped WAR EAGLE 10, the 1-3/4 inch high tag had a slot for a leather strap that Topliff had attached to the baggage, a common practice on steamboats and railroads of the day.

Sixty-one years later, in 1931, the Black River dropped to a record low stage, and many local residents were able to wade into the water and pick souvenirs from the charred remains of the War Eagle. This tag was one of them.

Who knows what treasures from 1870 it represents? Perhaps it was an immigrant trunk full of clothing, books and some precious mementos, or perhaps a craftsman's toolbox. Or a traveling salesman's patent medicines. Whatever it was, it's still waiting to be picked up, in damaged condition, at the bottom of the Black River at La Crosse.

The La Crosse County Historical Society has hundreds of additional items salvaged from the War Eagle on exhibit at the Riverside Museum in Riverside Park. The museum is open from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Mondays through Saturdays and 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Sundays.

Box cover watercolor "The Romantic River" for a 750 piece jigsaw puzzle by Warren Built-Rite Warren Paper Products Co. of Lafayette, Indiana.

Relax you are on the Mississippi River Now

Listed on ETSY by Kelissa Shea:

Sign - Pine 18 x 9.25 x .75 - Relax you are on the Mississippi River Now

https://www.etsy.com/listing/880466713/sign-pine-18-x-925-x-75-relax-you-are-on?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=mississippi+river&ref=sr_gallery-3-35&organic_search_click=1&frs=1

Wood Wall Art Hanging Decor

$45.00

Wood, Stain, Paint, Polycrylic, Pine

Height: 9.25 Inches; Width: 18 Inches; Depth: .75 Inches

Pilots' Association MO (MISSOURI) lapel pin

Pilots' Association MO (MISSOURI) lapel pin

.60 inches in diameter

I found this item in an antique store on the Paducah, Kentucky waterfront while on my way back to the DELTA QUEEN for lunch in September, 1993.

Sam Clemens wrote about the Pilots' Association in Chapter 15 of LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI Excerpts from the Chapter are below The complete text of the Chapter is available at this link:

telelib.com

Having set forth in detail the nature of the science of piloting, and likewise described the rank which the pilot held among the fraternity of steamboatmen, this seems a fitting place to say a few words about an organization which the pilots once formed for the protection of their guild. It was curious and noteworthy in this, that it was perhaps the compactest, the completest, and the strongest commercial organization ever formed among men.

For a long time wages had been two hundred and fifty dollars a month; but curiously enough, as steamboats multiplied and business increased, the wages began to fall little by little. It was easy to discover the reason of this. Too many pilots were being 'made.' It was nice to have a 'cub,' a steersman, to do all the hard work for a couple of years, gratis, while his master sat on a high bench and smoked; all pilots and captains had sons or nephews who wanted to be pilots. By and by it came to pass that nearly every pilot on the river had a steersman. When a steersman had made an amount of progress that was satisfactory to any two pilots in the trade, they could get a pilot's license for him by signing an application directed to the United States Inspector. Nothing further was needed; usually no questions were asked, no proofs of capacity required.

Very well, this growing swarm of new pilots presently began to undermine the wages, in order to get berths. Too late—apparently—the knights of the tiller perceived their mistake. Plainly, something had to be done, and quickly; but what was to be the needful thing. A close organization. Nothing else would answer. To compass this seemed an impossibility; so it was talked, and talked, and then dropped. It was too likely to ruin whoever ventured to move in the matter. But at last about a dozen of the boldest—and some of them the best—pilots on the river launched themselves into the enterprise and took all the chances. They got a special charter from the legislature, with large powers, under the name of the Pilots' Benevolent Association; elected their officers, completed their organization, contributed capital, put 'association' wages up to two hundred and fifty dollars at once—and then retired to their homes, for they were promptly discharged from employment. But there were two or three unnoticed trifles in their by-laws which had the seeds of propagation in them. For instance, all idle members of the association, in good standing, were entitled to a pension of twenty-five dollars per month. This began to bring in one straggler after another from the ranks of the new-fledged pilots, in the dull (summer) season. Better have twenty-five dollars than starve; the initiation fee was only twelve dollars, and no dues required from the unemployed.

Also, the widows of deceased members in good standing could draw twenty- five dollars per month, and a certain sum for each of their children. Also, the said deceased would be buried at the association's expense. These things resurrected all the superannuated and forgotten pilots in the Mississippi Valley. They came from farms, they came from interior villages, they came from everywhere. They came on crutches, on drays, in ambulances,—any way, so they got there. They paid in their twelve dollars, and straightway began to draw out twenty-five dollars a month, and calculate their burial bills.

By and by, all the useless, helpless pilots, and a dozen first-class ones, were in the association, and nine-tenths of the best pilots out of it and laughing at it. It was the laughing-stock of the whole river. Everybody joked about the by-law requiring members to pay ten per cent. of their wages, every month, into the treasury for the support of the association, whereas all the members were outcast and tabooed, and no one would employ them. Everybody was derisively grateful to the association for taking all the worthless pilots out of the way and leaving the whole field to the excellent and the deserving; and everybody was not only jocularly grateful for that, but for a result which naturally followed, namely, the gradual advance of wages as the busy season approached. Wages had gone up from the low figure of one hundred dollars a month to one hundred and twenty-five, and in some cases to one hundred and fifty; and it was great fun to enlarge upon the fact that this charming thing had been accomplished by a body of men not one of whom received a particle of benefit from it. Some of the jokers used to call at the association rooms and have a good time chaffing the members and offering them the charity of taking them as steersmen for a trip, so that they could see what the forgotten river looked like. However, the association was content; or at least it gave no sign to the contrary. Now and then it captured a pilot who was 'out of luck,' and added him to its list; and these later additions were very valuable, for they were good pilots; the incompetent ones had all been absorbed before. As business freshened, wages climbed gradually up to two hundred and fifty dollars—the association figure—and became firmly fixed there; and still without benefiting a member of that body, for no member was hired. The hilarity at the association's expense burst all bounds, now. There was no end to the fun which that poor martyr had to put up with.

However, it is a long lane that has no turning. Winter approached, business doubled and trebled, and an avalanche of Missouri, Illinois and Upper Mississippi River boats came pouring down to take a chance in the New Orleans trade. All of a sudden pilots were in great demand, and were correspondingly scarce. The time for revenge was come. It was a bitter pill to have to accept association pilots at last, yet captains and owners agreed that there was no other way. But none of these outcasts offered! So there was a still bitterer pill to be swallowed: they must be sought out and asked for their services. Captain & #151;— was the first man who found it necessary to take the dose, and he had been the loudest derider of the organization. He hunted up one of the best of the association pilots and said—

'Well, you boys have rather got the best of us for a little while, so I'll give in with as good a grace as I can. I've come to hire you; get your trunk aboard right away. I want to leave at twelve o'clock.'

'I don't know about that. Who is your other pilot?'

'I've got I. S-------. Why?'

'I can't go with him. He don't belong to the association.'

'What!'

'It's so.'

'Do you mean to tell me that you won't turn a wheel with one of the very best and oldest pilots on the river because he don't belong to your association?'

'Yes, I do.'

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The captain stormed, but to no purpose. In the end he had to discharge S-----, pay him about a thousand dollars, and take an association pilot in his place. The laugh was beginning to turn the other way now. Every day, thenceforward, a new victim fell; every day some outraged captain discharged a non-association pet, with tears and profanity, and installed a hated association man in his berth. In a very little while, idle non-associationists began to be pretty plenty, brisk as business was, and much as their services were desired. The laugh was shifting to the other side of their mouths most palpably. These victims, together with the captains and owners, presently ceased to laugh altogether, and began to rage about the revenge they would take when the passing business 'spurt' was over.

Soon all the laughers that were left were the owners and crews of boats that had two non-association pilots. But their triumph was not very long-lived. For this reason: It was a rigid rule of the association that its members should never, under any circumstances whatever, give information about the channel to any 'outsider.' By this time about half the boats had none but association pilots, and the other half had none but outsiders. At the first glance one would suppose that when it came to forbidding information about the river these two parties could play equally at that game; but this was not so. At every good-sized town from one end of the river to the other, there was a 'wharf-boat' to land at, instead of a wharf or a pier. Freight was stored in it for transportation; waiting passengers slept in its cabins. Upon each of these wharf-boats the association's officers placed a strong box fastened with a peculiar lock which was used in no other service but one—the United States mail service. It was the letter-bag lock, a sacred governmental thing. By dint of much beseeching the government had been persuaded to allow the association to use this lock. Every association man carried a key which would open these boxes. That key, or rather a peculiar way of holding it in the hand when its owner was asked for river information by a stranger—for the success of the St. Louis and New Orleans association had now bred tolerably thriving branches in a dozen neighboring steamboat trades—was the association man's sign and diploma of membership; and if the stranger did not respond by producing a similar key and holding it in a certain manner duly prescribed, his question was politely ignored. From the association's secretary each member received a package of more or less gorgeous blanks, printed like a billhead, on handsome paper, properly ruled in columns.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

These blanks were filled up, day by day, as the voyage progressed, and deposited in the several wharf-boat boxes. For instance, as soon as the first crossing, out from St. Louis, was completed, the items would be entered upon the blank, under the appropriate headings, thus—

'St. Louis. Nine and a half (feet). Stern on court-house, head on dead cottonwood above wood-yard, until you raise the first reef, then pull up square.' Then under head of Remarks: 'Go just outside the wrecks; this is important. New snag just where you straighten down; go above it.'

The pilot who deposited that blank in the Cairo box (after adding to it the details of every crossing all the way down from St. Louis) took out and read half a dozen fresh reports (from upward-bound steamers) concerning the river between Cairo and Memphis, posted himself thoroughly, returned them to the box, and went back aboard his boat again so armed against accident that he could not possibly get his boat into trouble without bringing the most ingenious carelessness to his aid.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

. . . a pilot; must devote himself wholly to his profession and talk of nothing else; for it would be small gain to be perfect one day and imperfect the next. He has no time or words to waste if he would keep 'posted.'

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

By and by the association published the fact that upon a certain date the wages would be raised to five hundred dollars per month. All the branch associations had grown strong, now, and the Red River one had advanced wages to seven hundred dollars a month. Reluctantly the ten outsiders yielded, in view of these things, and made application. There was another new by-law, by this time, which required them to pay dues not only on all the wages they had received since the association was born, but also on what they would have received if they had continued at work up to the time of their application, instead of going off to pout in idleness. It turned out to be a difficult matter to elect them, but it was accomplished at last. The most virulent sinner of this batch had stayed out and allowed 'dues' to accumulate against him so long that he had to send in six hundred and twenty-five dollars with his application.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The association had a good bank account now, and was very strong. There was no longer an outsider. A by-law was added forbidding the reception of any more cubs or apprentices for five years; after which time a limited number would be taken, not by individuals, but by the association, upon these terms: the applicant must not be less than eighteen years old, and of respectable family and good character; he must pass an examination as to education, pay a thousand dollars in advance for the privilege of becoming an apprentice, and must remain under the commands of the association until a great part of the membership (more than half, I think) should be willing to sign his application for a pilot's license.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The widow and orphan list grew, but so did the association's financial resources. The association attended its own funerals in state, and paid for them. When occasion demanded, it sent members down the river upon searches for the bodies of brethren lost by steamboat accidents; a search of this kind sometimes cost a thousand dollars.

The association procured a charter and went into the insurance business, also. It not only insured the lives of its members, but took risks on steamboats.

The organization seemed indestructible. It was the tightest monopoly in the world. By the United States law, no man could become a pilot unless two duly licensed pilots signed his application; and now there was nobody outside of the association competent to sign. Consequently the making of pilots was at an end. Every year some would die and others become incapacitated by age and infirmity; there would be no new ones to take their places. In time, the association could put wages up to any figure it chose; and as long as it should be wise enough not to carry the thing too far and provoke the national government into amending the licensing system, steamboat owners would have to submit, since there would be no help for it.

With the exception of images credited to public institutions,

everything on this page is from a private collection.

Please contact Steamboats.com for permission for commercial use.*

All captions provided by Dave Thomson, Steamboats.com primary contributor and historian.

With the exception of images credited to public institutions,

everything on this page is from a private collection.

Please contact Steamboats.com for permission for commercial use.*

All captions provided by Dave Thomson, Steamboats.com primary contributor and historian.