Magazine Covers and Illustrations, page 2

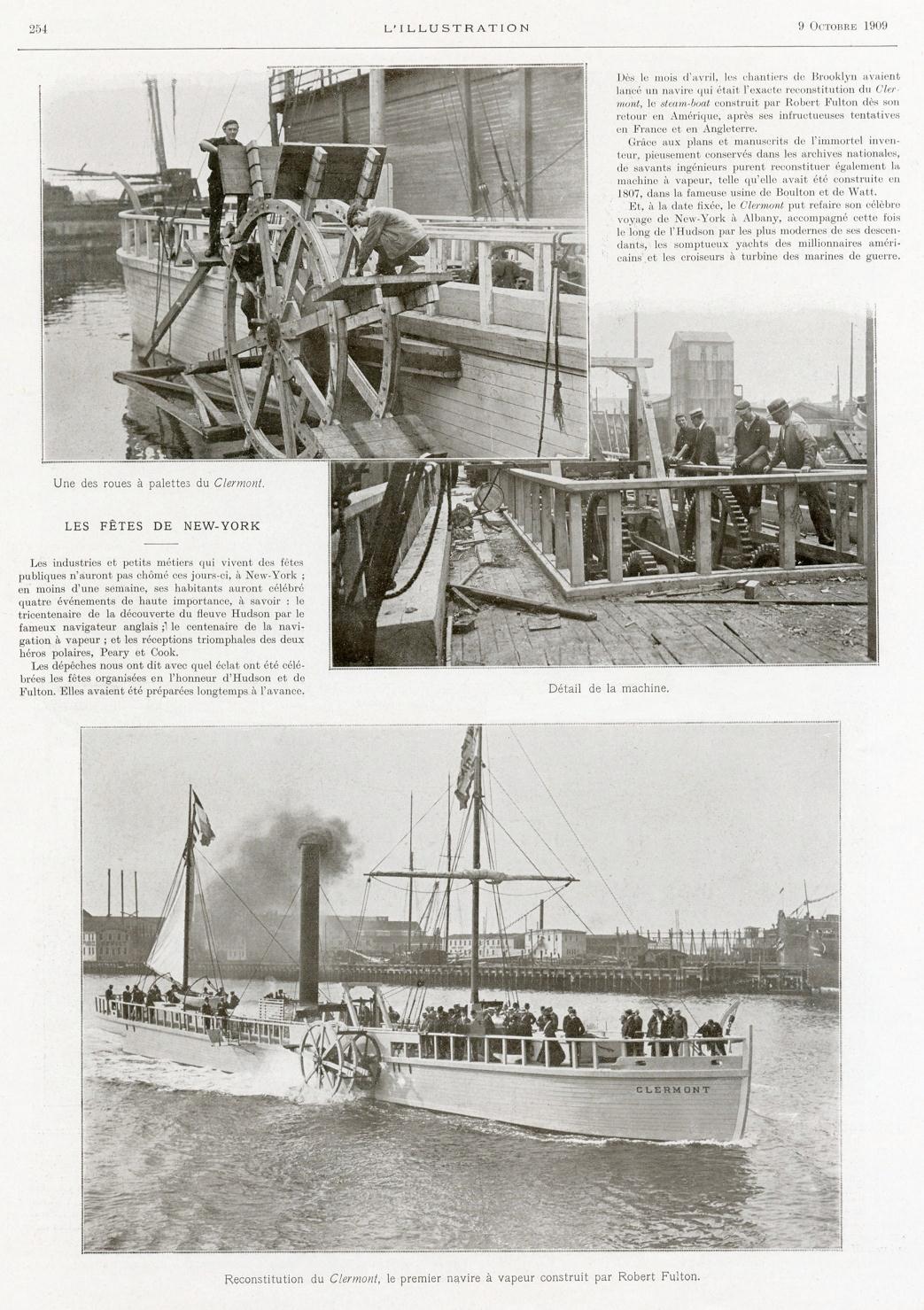

HERE'S SOMETHING UNUSUAL - FROM THE OCTOBER 9TH, 1909 ISSUE OF THE FRENCH MAGAZINE "L'ILLUSTRATION" PAGE 254 A PICTORIAL ARTICLE ON A REPLICA OF ROBERT FULTON'S "NORTH RIVER" (MISTAKENLY CALLED THE "CLERMONT" BY LATER HISTORIANS) BUILT FOR THE HUDSON-FULTON CELEBRATION IN NEW YORK. RECEIVED THIS YESTERDAY FROM AN EBAY DEALER IN FRANCE.

North River Steamboat

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Wikipedia

The North River Steamboat or North River (often erroneously referred to as Clermont) is widely regarded as the world's first vessel to demonstrate the viability of using steam propulsion for commercial water transportation. Built in 1807, the North River Steamboat operated on the Hudson River (at that time often known as the North River) between New York and Albany. She was built by the wealthy investor and politician Robert Livingston and inventor and entrepreneur Robert Fulton (1765-1815).

1909 Clermont replica

A full-sized, 150 foot long by 16 foot wide steam-powered replica, named Clermont, was built by the Staten Island Shipbuilding Company. The replica's design and final appearance was decided by an appointed commission who carefully researched Fulton's steamer from what evidence and word-of-mouth had survived to the early 20th century.

Their replica was launched with great fanfare in 1909 at Staten Island, New York, for the Hudson-Fulton Celebration.

In 1910, following the large celebration, Clermont was sold by her owners, the Hudson-Fulton Celebration Commission, to defray their losses; she was purchased by the Hudson River Day Line and served the company as a moored river transportation museum at their two locations in New York harbor.

In 1911 Clermont was moved to Poughkeepsie, New York and served Day Line as a New York state historic ship attraction. The company eventually lost interest in the steamboat as a money-making attraction and placed her in a tidal lagoon on the inner side of their landing at Kingston Point, New York. For many years Day Line kept Clermont in presentable condition, but as their business and profits slowed during the Great Depression, they voted to stop maintaining her; Clermont was eventually broken up for scrap in 1936, 27 years after her launching.

The TENNESSEE BELLE's former Captain Dick Dicharry

THE WATERWAYS JOURNAL LETTER FROM 12 FEB 1955 I HAVE INCLUDED EXCERPTS FROM THE TEXT OF BEN LUCIEN BURMAN'S TRIBUTE TO CAPTAIN DICHARRY IN A 1951 NON-FICTION BOOK (FILE OF THE DUST JACKET OF "CHILDREN OF NOAH" ATTACHED.

AFTER THAT HAVE ADDED AN EXCERPT FROM A HISTORY OF THE ST. LOUIS & TENNESSEE RIVER PACKET CO. IN WHICH CAPTAIN DICHARRY OFFERED TO BUY FRED WAY'S BETSY ANN BEFORE BUYING THE TENNESSEE BELLE.

ALSO ATTACHED A 1941 COLOR SLIDE OF THE TENNESSEE BELLE, TAKEN AT VICKSBURG BY CHARLES W. CUSHMAN OF INDIANA WHICH DEMONSTRATES THE NEGLECTED STATE OF THE BOAT AS DESCRIBED IN THE PACKET CO. HISTORY WHERE IT IS MENTIONED THAT DUE TO FINANCIAL HARD TIMES THE BOATS OF THAT PERIOD WERE OFTEN POORLY MAINTAINED. AM SURPRISED THAT CAP'N DICHARRY DIDN'T PUT HIS CREW TO WORK PAINTING THE BELLE TO SPRUCE HER UP. FRIENDLY MERCHANTS ON SHORE WOULD PROBABLY HAVE DONATED THE PAINT.

DAVE

THE WATERWAYS JOURNAL

12 FEBRUARY 1955

page ELEVEN

CAPT DICK DICHARRY HAS AN UNEXPECTED VISITOR Washington, D. C., January 22, 1955

To the Editor of The Waterways Journal. I spent a $5 taxi fare just before Christmas to drive from the airport in New Orleans to St. Rose, over the Mississippi River levee, just for a 15-minute chat with Capt. Dick Dicharry, the last owner of the Tennessee Belle. Capt. Dick, Gertrude, his wife, mother and three dogs were all fine. Their coffee tasted just like steamboat coffee in the pilothouse at four o'clock I in the morning—which was the finest coffee ever made. Capt. Dick still lives by the levee and still waves at the boats and is about as happy as a steamboat man can be without a boat.

He is as spry as a cricket although he says his rheumatism bothers him at times. He loaned me his personal and autographed copy of "Children of Noah" (by Ben Lucien Burman) so I would have something to read on the plane which I took back to Los Angeles that afternoon. It is really refreshing to talk with the boys who ran the rivers when steamboating was in its glory and pilots did a wonderful job without channel markers.

While in New Orleans, I went to the Cabildo Museum and arranged for Al Farette, our photographer, to make a picture of the model of the Tennessee Belle. This boat had the honor of being the last regular general freight and passenger packet on the Mississippi. I spent many happy days and nights looking out of the pilothouse. The model was built by Ernest W Bates, Sr., engineer of the Tennessee Belle, and is securely enclosed in a large glass case about seven feet long. I have sent pictures of the model to Mrs. Charles R. Beard, of Clifton, Tenn., wife of the Belle's pilot when she ran from St. Louis to Pittsburg Landing, on the Tennessee, and to Capt. Dick, of course.

I am on the "go" again and expect to eat dinner on the "Sternwheeler" (RIVER QUEEN) at Owensboro if I can work it into my schedule. Maybe I'll see you on the Delta Queen's down trip from St. Paul this summer since I'll be on board if nothing happens.

Sincerely, Frank L. Teuton.

The following has been edited and abridged from KING OF STEAMBOATMEN pages 43-69 in Ben Lucien Burman's 1951 non-fiction book: "Children of Noah—Glimpses of Unknown America" Published by Julian Messner Inc.

Dick Dicharry was born in the village of Smoke Bend, Louisiana, where as a boy he watched with awe the white-painted river craft gliding down the Mississippi. He decided there was only one thing in life worth doing; he would become the proprietor of a steamboat.

He found a vacancy at last on a vessel of the Bradford Lines, where the crew was lacking an assistant clerk. He persuaded the captain to give him a trial at an almost invisible salary. By the end of the month, his salary was quadrupled. The boy from Smoke Bend was launched on his career.

Quickly he rose from assistant to a full clerkship; from time to time when there was need he began to act as master.

Always as the boat swung in for a landing he was the first to leap upon the muddy bank. Soon he possessed friends everywhere, who would often travel miles out of their way to bring him onions or yams or watermelons, or whatever the loads in their rattling wagons.

He heard of a small steamboat named the Uncle Oliver up the river which was for sale at a bargain. Captain Dick had managed to save a little money from his salary. A local merchant offered to lend him the remainder. Captain Dick decided to buy the boat and run it on the Mississippi.

Captain Dick Dicharry would become King of Steamboatmen of the Lower Mississippi.

Dicharry is a man of average height, with the sturdy physique common to most men who spend their lives on the river. His walk is jaunty, his movements electric. He seems supercharged with energy. His eyes are bright, merry; his mouth curved in a smile that radiates warmth and geniality. He is obviously a happy man, a lover of pleasantry and laughter.

I never ceased to find some new phase of his extraordinary character. Ordinarily a man of peaceful ways, when his anger was roused he was like an exploding volcano. Possessing the courage of a lion, I am sure he would not have hesitated empty-handed to fight ten men holding machine guns if they were abusing a child or an old Negro. He was the idol of his friends, and the terror of his enemies.

His kindness toward the poor or unfortunate was perhaps his most striking quality. For generations on the river a bitter feud has continued between the patrician steamboatmen and the lowly shantyboaters who live in the floating homes moored along the bank. Some captains send their craft at full speed past a shantyboat, regardless of the fact that the waves from the huge propellers or paddle wheels may almost swamp the smaller vessel moored along the willows. For Captain Dick the contrary was always the rule.

I have seen him bring the Uncle Oliver to a stop as it neared a shantyboat where some river dweller was cooking supper, because he did not wish to send the rabbit stew or catfish flying to the shanty floor. I have seen him keep the whistle of the Oliver silent, because in a little houseboat near by a shantyman's wife lay ill, and the sound might have roused her from a troubled sleep.

Years passed and the Uncle Oliver, too old to struggle longer, went the way of all good rivermen and river boats. Captain Dick heard of a large packet for sale up the Tennessee River, bearing the graceful name of the Tennessee Belle.

He went off to inspect it, and concluding the purchase on sight, brought the vessel at once to the Mississippi. The Tennessee Belle was a beautiful steamboat. A voyage upon her was an adventure in tranquility. White painted like a bride she would glide over the brown river, while the ever-changing panorama of the Valley swept past her prow, her sweet-toned whistle would blow, echoing musically across the swamps and the levees.

In 1927 a terrible flood swept the Mississippi Valley, the worst disaster in all its troubled history.

Captain Dick at once took his steamboat and began rescuing people from their flooded dwellings, carrying them off to the refugee camps on the levees, or to towns safe in the distant hills.

Relief was not organized in the efficient manner of today, with Coast Guard stations and their trained crews ready to spring into instant action.

The loss of life in some areas was appalling. Captain Dick labored night and day—savior of the living, doctor of the sick, and preacher for the dead.

Often, as he took the Uncle Oliver across the raging water, he would come upon a farmhouse whose inhabitants had been cut off for a week or more, unable to get word of their plight to headquarters.

Occasionally one of these families would be at the point of starvation, with the mother and several children stricken with fever and dying for lack of medicine.

At such times Captain Dick would bring out some of the government supplies and drugs he happened to be transporting to a refugee camp, leave what he thought necessary at the flooded home, and go on his way again over the muddy sea.

The area, for the emergency, was under military law. A newly arrived army lieutenant, more familiar with regulations than with disaster, was in charge of one of the nearby depots. Chancing to learn of Captain Dick's actions, he summoned the river captain, and informed him that he was disposing of government property without the authority the regulations demanded.

He warned that if the captain continued his practices, the lieutenant would order him court-martialed. Captain Dick, exhausted from his continuous labor without sleep, listened, and point-blank refused to obey his commands. More days passed, and he found more stricken families; again he gave them the supplies they needed so desperately.

Then one morning when the vessel docked near the depot the lieutenant commanded, a grim-faced soldier was waiting. "Want you up at headquarters," he announced.

Captain Dick hurried off with him up the muddy path. In a tent on the levee some high officers on a tour of inspection were assembled, sitting stiffly on camp chairs. The depot commander turned to the visitors, headed by a solemn, much-decorated general, and asked that drastic punishment be meted out to the offending riverman.

Captain Dick faced the stern dignitaries unafraid. "If I pass a man dying of hunger, won't ask if he's got the right piece of paper," he declared stubbornly. "Can't eat paper. Going to feed him, that's all. Won't stop unless you shoot me through the head."

He continued to speak for some time, growing more and more eloquent as he told of the scenes he had witnessed. When he finished each of the visitors came forward and shook his hand. He left the tent, instead of a criminal a hero, with power to distribute relief supplies anywhere.

He could never understand a human being who did not love a steamboat. He was talking one day with a river captain, whose vessel in a near-by trade had been damaged beyond repair and was on its way to the steamboat graveyard.

Captain Dick expressed his sympathy to the former master. To his amazement the other riverman, noted for his lack of warmth, only shrugged his shoulders.

"What's a steamboat?" he demanded. "Just some deck boards, a paddle wheel, and a fool in a pilothouse."

Captain Dick grew hot with anger.

"Thought you were my friend," he retorted. "Now I know better. You don't feel bad when your steamboat dies; I know you won't worry when I die. You're too cold a man for me. We're through."

Year after year the Tennessee Belle continued to steam up and down the Mississippi and as I gazed out of the wide pilothouse window, I would always remember what the Belle and the Oliver and Captain Dick had taught me of the river.

St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co.

Being a True History & Account

1885 - 1942

stlouistennriverpacketco.com

On a July day in 1927 Capt. Dick Dicharry arrived in St. Louis. He had been running a small boat of about 150 foot hull out of Vicksburg, but his boat had burned; believing there was yet packet traffic to be had on the Lower River, Dicharry wanted another boat.

Capt. Fred Way, another optimist on the future of packet service, on the upper Ohio, had been first visited by Dicharry, object: Sell him the Betsy Ann, Way's boat then running between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. In spite of any argument that Dicharry could bring to bear, Way said no.

Thus the St. Louis visit, which Dicharry seemed to think was next best town for surplus boats, where he found, first, on walking down from Washington Ave., the Belle of Calhoun tied off at the levee. The Belle had been bringing down apples in direct opposition to the trade of Alabama, and since the owners had come from that county, they achieved some success; not enough, however to stop the Alabama. Possibly they lacked finesse in customer relations, as illustrated:

Dicharry started up the stage set on the levee, and barely reaching the foredeck, heard a loud voice, "Git off the boat." The worthy captain hastily retreated and went down levee fifty yards to the wharf of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co., where a cordial reception was gained from Rhea in the office.

Dicharry spoke with a thick accent Rhea had some difficulty in comprehending at first, but eventually the word came through that his visitor wanted a boat. Of course, selling off a major asset called for consultation with the younger brother, theoretically, but the brother was out of town at the time, and as Rhea contemplated the situation he was not inclined to ponder.

Whether the Alabama came up for discussion is not known, but with rebuilding, the Tennessee Belle was technically a newer boat; it is suspected she was not at the wharf that day, but must have arrived from her regular Tennessee River trip in short order, and Rhea must have had Dicharry return as soon as possible to see the merchandise.

When Rhea found out Dicharry was prepared to pay cash, there was no hesitation. Actually, the boat had been doing well that season, and a new trip with staterooms about filled had already been booked. But, as Rhea viewed it, the trade had no assurance of continuing and it was unlikely any better offer than cash was going to materialize. He agreed to accept $25,000 offered by Dicharry, who wanted the boat immediately, and promptly sent off telegrams to the booked passengers to not come to St. Louis, that their trip had been canceled.

Capt. Dicharry took the boat to Vicksburg, and put her on a run to Natchez. As the depression years of the 1930's deepened, Dicharry ran out of cash, like everybody else, did not maintain the boat, and she became a shabby imitation of anything the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co. would ever have run in its fleet. But she kept running anyway, and achieved some fame as the last packet remaining on the Lower Mississippi. She finally burned below Natchez in 1942.

Sale of Tennessee Belle may have been interpreted, from outside parties, as a sign the Company was disposing of its equipment that summer, for in August, 1927 an unsolicited offer was made for Robert Rhea. Rhea was glad to accept. New owners took her to Mobile for the Alabama River, and she continued in service for several years; her ultimate disposition is unknown.

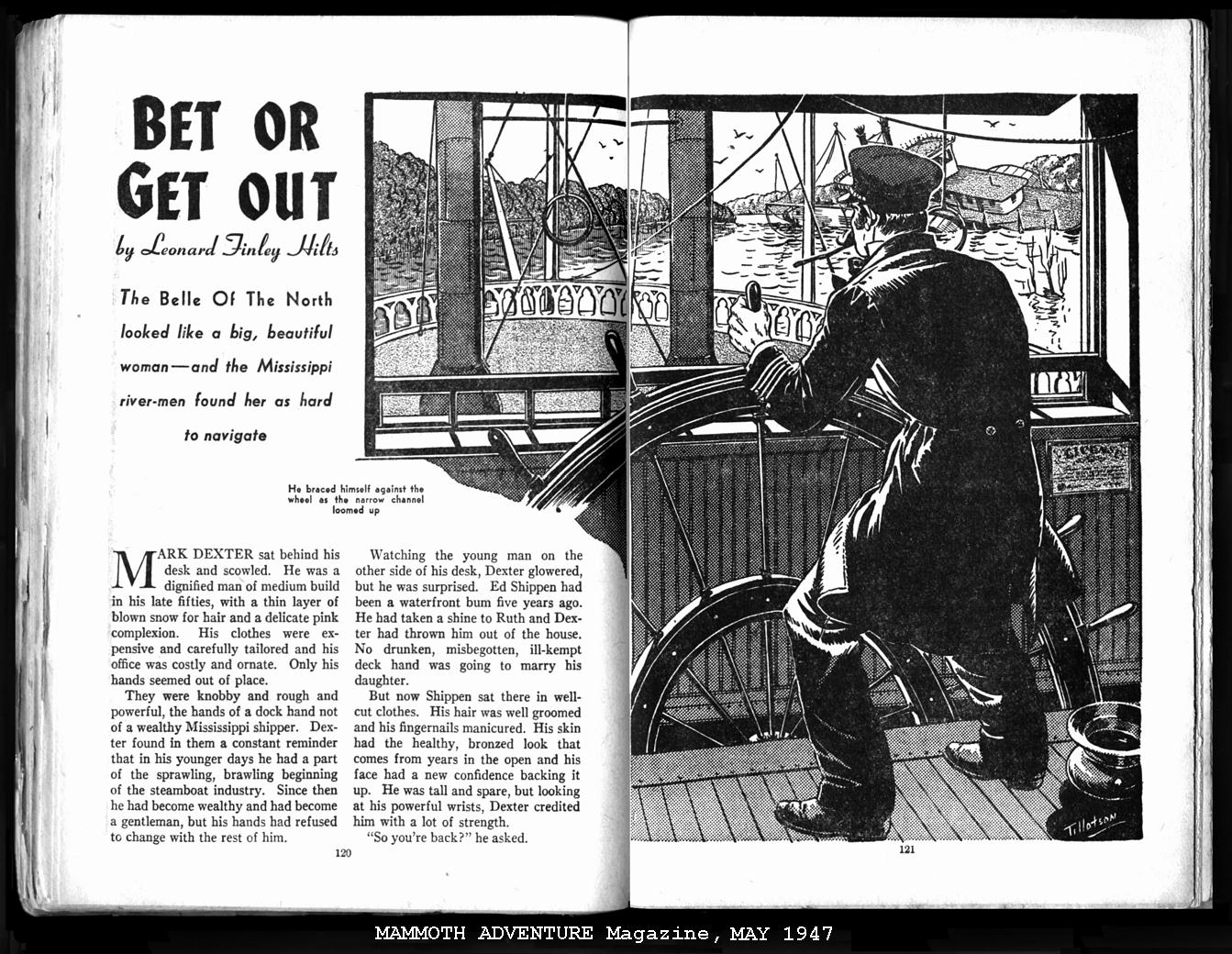

Steamboat pilot house illustration for a story in the pulp magazine MAMMOTH ADVENTURE, May 1947. Sunken steamer in the distance on the river behind the pilot at the wheel.

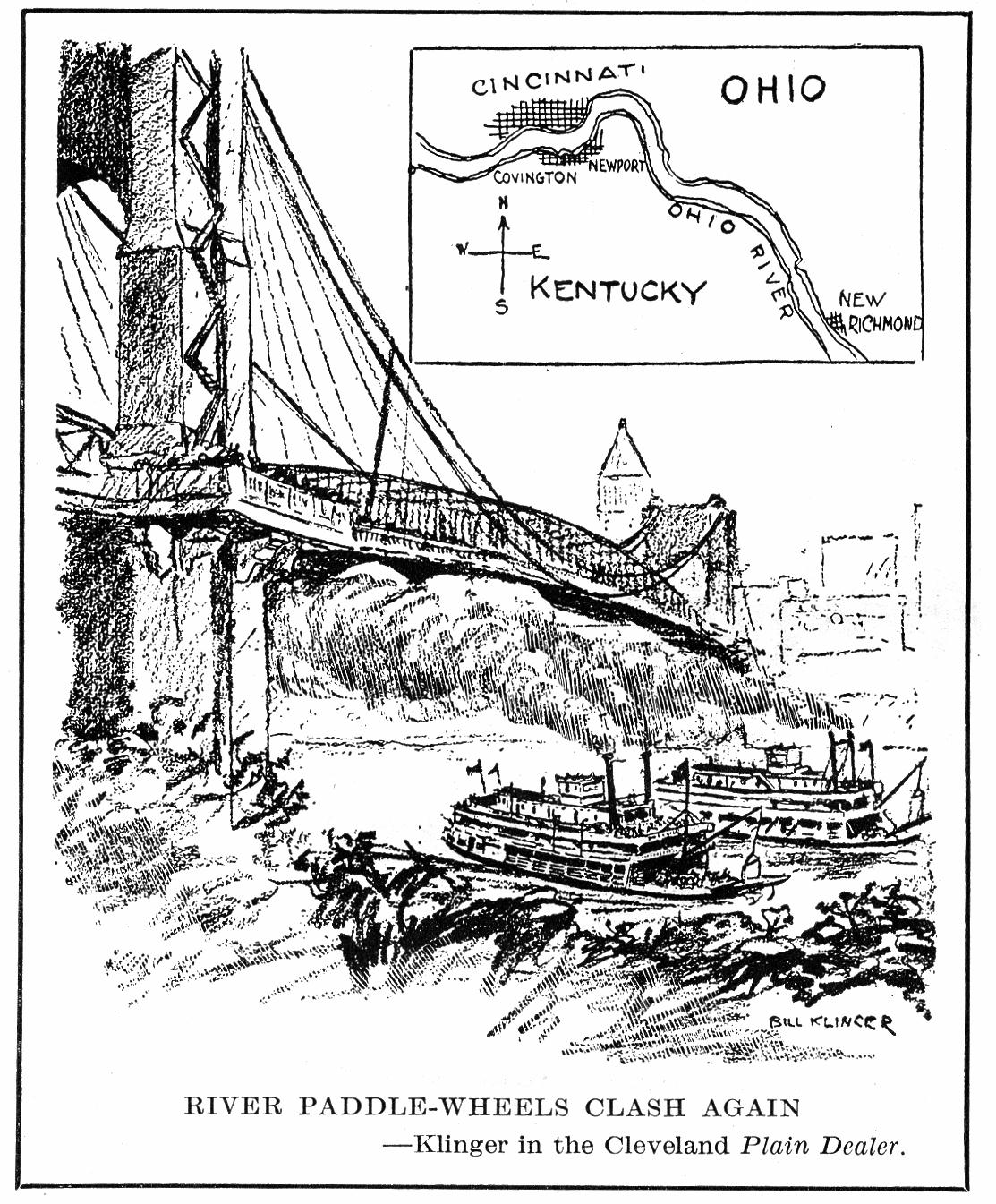

The Literary Digest, August 17, 1929

REVIVING THE WHOOPEE OF STEAMBOAT RACING

A roustabout named "Pig Meat," who had bet his shoes on the Betsy Ann, refused to give them up. He swore that both boats had won. Many others said the same thing, and, indeed, 'twas a very tricky finish to a neck-and-neck race—the closest packet race ever seen, according to historians of the big river.

A Cincinnati Times-Star writer breaks into verse about it:

Heads you cash, tails you lose,

Dis darky don't give up his shoes!

If Tom Greene's bow was de winning boss,

De Betsy's stern-wheel was de first to cross!

And then, relapsing into prose, he explains that "the Tom Greene's bow crossed the line ten feet ahead of the Betsy's but the Betsy is forty feet smaller than the Tom, and so the Betsy's entire length, including her wheel, crossed the line thirty feet ahead of the Tom Greene's sternwheel. That was enough of a technicality for the roustabouts to make a grand palaver over. They will argue the question on the riverboats the rest of their lives. The Tom Greene received the formal cup of victory, but the Betsy Ann received her full mead of applause and honors."

Just at this time last year, THE DIGEST chronicled a race between that little thirty-year-old speed queen, Betsy Ann, and another of her larger modern, rivals, the Chris Greene. That revival of old-time Mississippi Steamboat racing was such a success that this year the Betsy Ann was pitted against the Tom Greene, and 100,000 people saw the race, which was accompanied, we are told, by an incidental music of sirens, drone of diving airplanes, raving of rival roustabouts, and barking of dogs and radio-announcers. Charles Ludwig, the writer we have already quoted, continues his account with this piece of word painting:

A Niagara of spindrift dashed over the bows of the two steamboats as they battled their way nose and nose over the twenty-two-mile course from the Cincinnati levee to New Richmond, Ohio.

The Tom Greene generally was in the lead from five to thirty feet, and the race was so close that at one time the two boats were locked side by side for a moment, attracted by the suction their wheels created.

It was at first announced that the race would end at the dam below Richmond, and here, with both steamers tugging their mightiest, the boats were running about even, the Greene being perhaps a few feet ahead.

Then, it was declared that the contest would not be officially concluded till the boats reached New Richmond, a mile farther up the river. This last mile afforded the keenest rivalry between the boats. Sometimes the Betsy would make a spurt, and then the Tom Greene would forge ahead. It was an even race in this final stage, too.

The Tom Greene managed to cling onto her slight lead, and finished ten feet ahead, amid cheers from the passengers, the blowing of whistles, songs of Boy Scouts, and shouts of the crowd on the shore.

W. C. Culkins, vice-president of the Chamber of Commerce and secretary of time Ohio Valley Improvement Association, and Slack Barrett, of the Barrett Lines, were the official judges. The race was so close that Barrett, who had taken along a measuring line, was prepared to use it on the two gang-planks of the boats to convince Betsy Ann followers of the accuracy of the decision, but this was not necessary.

The time for covering the twenty-two miles was two hours and nineteen minutes.

Weather was ideal when the race started from the Cincinnati levee shortly after 5 P.M. There were crowds on both boats. Mrs. Mary Greene, widow of Capt. Gordon C. Greene, and the only woman steamboat captain and pilot on the river, was in command of the Tom Greene. But Mrs. Greene acted chiefly as hostess to the passengers, and her son, Capt. Torn Greene, had charge of the actual operation, assisted by his brother, Capt. Chris Greene. Captain Chris and his boat, the Chris Greene, defeated the Betsy Ann in the memorable race a year ago.

The youthful Capt. Frederick Way, owner of the Betsy Ann, was aboard his boat and Capt. Charles Ellsworth was in. charge, with Wirt Jordan as chief engineer. Officers of the Betsy claimed that at the New Richmond dam they were about three feet in the lead.

George Wise, twenty-five, youngest chief engineer on the river, was in charge of the engines of the Tom Greene. Wise said that about the middle of the race a steam pipe under the floor of the engine-room sprang a leak, which made it impossible to use maximum pressure and the inquiring reporters heard the rush of the steam.

The Betsy carried the colors of Pittsburgh, and there was a delegation of Pittsburgh newspapermen aboard to report the race.

"You Pittsburghers will have to build a faster boat now if you want the river championship," they were told, but the Pittsburghers still seem to think the venerable Betsy Ann, much older than the modern Greene-line boats, never yet has been beaten fairly.

The Island Queen, with a crowd aboard, followed the racers up the river. Airplanes hovered above and many speedboats followed the racers.

Roustabouts named "Chalk Eye," "Six Bits," "Little Breeches," "Whisky," "Broad Ax," and "Big Un" were discoursing on the hot finish, of the race. And "Six Bits" sang happily:

"De Torn Greene am de debit's boat,

All she do is load and tote.

If Betsy know'd this

She'd staid in po't!"

But "Chalk Eye," remembering how the winning Chris Greene "threw water in the Betsy's face" last year, chanted thus:

"Jes' now we had another race;

No water was throwed in Betsy's face;

Betsy evened up the deal;

She throwed water on Tom Greene's wheel!"

The stacks shook as the stokers fed the roaring fires under the boilers, and pieces of unburned coal came flying out of the smoke to rain down on the decks, we are told by Charles J. Mulcahy in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and he goes on to give us some quaint details of the race, thus:

The rocky bank at New Richmond was packed with people waiting to cheer the winner. So close was the finish, they could not tell which boat to cheer, so they argued about it instead.

The brick levee that slants down from Front Street, Cincinnati, was fairly swarming with taxicabs, and a crowd of several thousand persons had gathered at the top of the rise to watch the start of the race.

The steam calliope on the Island Queen was industriously snorting and bellowing something that sounded like " Ten Miles From Home." After that it played "I'll Get By."

Some one on the Tom Greene thoughtfully interrupted this song by ringing the ship's bell. Eighty-three times be rang the bell. The bell is fifty years old. Considering its age, it makes a lot of noise. Before it was bolted to the deck of the Tom Greene, it was on the steamer Montana.

At five the Betsy Ann cast off her lines and backed out into the stream. She came ahead slowly and stopped opposite the mouth of the Licking River that separates Covington from Newport, Kentucky.

At 5:10 the Tom Greene cut loose with her chime whistle—two blasts. The Tom Greene has the most famous whistle on the Ohio River. It whistles a B-flat chord. You can pick out the tone on a piano—F, B-flat, D and A-flat, or something like that.

"Something like that" is good—so good that THE DIGEST prudently disclaims responsibility for Mr. Mulcahy's chord, although it may be a perfectly good rendering of the Tom Greene's harmonic hoot.

Reading on:

It used to be on the old steamer St. Laurence and on some other boat before that Capt. Gordon Christopher Greene liked it so well he offered to buy it for $500. The owners laughed at him. He thereupon bought the packet Courier, keel, hull, masts and all, just to get the whistle.

Capt. Tom Greene leaned over the rail a few seconds after this famous whistle blew.

"Let go the stern line," he said.

The Tom Greene slid away from the levee. She backed a little, then came ahead again, jockeying to clear the Island Queen. It required some expert maneuvering.

The Tom Greene's whistle then sounded three short blasts and the Betsy Ann moved up, heading for the Central Bridge, that links Cincinnati and Covington.

The Tom Greene pulled abreast the Betsy Ann and a young man in a gray suit fired a cannon, which up to this time had stood unnoticed on the top deck of the Tom Greene. It wasn't much of a cannon; it fired ten-gage shotgun shells.

The Tom Greene's whistle sounded again—one long pull and a short one. The man fired the cannon again. He appeared to be shooting at the pilot of the Betsy Ann. He also appeared to be missing him.

This failed to discourage him, however. Throughout the race he continued to fire at such objects as presented themselves—three airplanes, carrying cameramen—a fleet of speedboats—a man with a blue and orange tie. No hits.

As the boats, still neck and neck, steamed past the Ohio River Yacht Club, a tall, elderly gentleman threw his bat far out from the rail of the Tom Greene. It was a black derby. Black derbies, it developed, do not float well.

On up the river the packets went, between banks lined with spectators. Many of the watchers cheered as the boats went by. Others whistled. A few fired revolvers into the air. A few others shouted questionable advice to the rival captains, who ignored it.

The man with the cannon, it seemed to this observer, shot at practically all the spectators who offered questionable advice.

We learn with relief that he hit "practically none of them."

However:

A roustabout on the Betsy Ann screamed and pretended to be hit by a stray shot, but nobody had enough confidence in the cannoneer to believe it. The roustabout, piqued because the passengers doubted him, threw a whisky bottle at the Tom Greene. The bottle was empty.

A small battalion, of newsreel-cameramen added greatly to the excitement of the race by climbing all over the two boats, taking pictures of everything and everybody.

Some of them had microphones and batteries and miles and miles of tangled cables for recording the sound of the paddlewheels, the hissing of the steam, the swishing of the wash along the sides.

They also recorded the music of the accordion some one thoughtfully brought along and the music of a banjo.

The man with the banjo may have been the character from the song, "Oh, Susannah," popular when the California gold rush was on.

The song went:

"I jumped aboard the Telegraph,

My banjo under my wing."

The Telegraph was the finest packet on the Ohio in those days. She had a gold anchor hanging on her bell-rope for a handle. It hangs from a beam in Capt. Tom Greene's cabin now.

In the, main cabin of the Tom Greene, where 250 passengers were eating dinner while the race progressed, was Capt. Mary B. Greene, acting as hostess.

She didn't pilot her son's boat after all, unless you count the time she took the wheel long enough to be photographed.

Arch and Drew Edgington piloted the winner. They're brothers. Their father, George Edgington, had seven sons and all of them became steamboat masters. Old Man Edgington built a packet and called her the Seven Wonders, in honor of his numerous sons.

When, under the able guidance of Drew Edgington, the Tom Greene slid in alongside the vanquished Betsy Ann at the end. of the race, a great delegation of townsfolk came aboard. Among them was Lou E. White, New Richmond undertaker, who had with him the loving cup put up as a trophy by the business men of the town.

Under the gifted, but highly confusing, direction of some seventy-five photographers, he presented the cup to Capt. Tom Greene. White was acting for C. H. Bogart, New Richmond Mayor, who couldn't be found.

All the prominent guests and officials and whatnot left the packets at New Richmond and returned to Cincinnati by auto or speedboat to attend a banquet in. the winner's honor on the Hotel Gibson roof.

Capt. Fred Way of the Betsy Ann told the judges after the race that he thought the Betsy was the real winner, though he would, of course, accept the decision of the judges, we learn from the Cincinnati Times-Star.

Furthermore:

"Captain Way told us after the race that a photographer who took a picture as the boats passed the dam below New Richmond said the Betsy Ann was three feet in the lead," W. C. Culkins, one of the judges, stated. "Captain Way said, however, that he would abide by the decision of the judges, and, though he felt badly over the close decision, he was a good sport, and walked over and had his picture taken with the officers of the Tom Greene. The race was so close that we judges had to find out who was really in the lead by drawing a line across the two stages that projected over the bows of the boats."

Capt. Frederick Way showed the reporters the old-fashioned bar, with its foot rail still in good condition, on board the Betsy Ann. But it was bone-dry.

The bar, at which Southern gentlemen used to sip mint juleps when the Betsy ran, in the lower Mississippi trade, is forward on the main deck, but is arid and is used as an office now.

Last year the Betsy Ann lost to the Chris Greene the golden antlers she won in races in Southern waters. Now the Betsy sports another fine set of golden antlers, which shine brilliantly in the sun. They were a gift from friends.

"We'll win those rocking-chairs from you, too!" shouted a perspiring Negro coal-heaver of the Tom Greene, as he came out of the firing pit and pointed to the large antlers. But the antlers were not involved in this race, and the Betsy steamed on with them after the race.

The Tom Greene's narrow margin of victory over the Pittsburgh veteran makes for the enrichment of river traditions and furnishes material for more boat races no less than for argument, in the editorial judgment of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which continues:

There must be a graceful bowing to the decision of the judges on the part of the regional supporters of the loser and insistence that the wheel-spoke handle that separated the packets at the finish line is reason for a new challenge and another race.

An end so close and a race so stoutly contested have seldom if ever been seen on the rivers. When the Chris Greene won over the Betsy last summer, there were six boat-lengths of open water between the steaming packets. In the classic days races were longer and the separations greater; the Robert E. Lee was four hours ahead of the Natchez in the famous meeting of 1870 on the 1,250-mile run from New Orleans to St. Louis, the race to which rivermen look when fast time on the inland waters is in question. Eyelash finishes are usually for the race tracks and not for the streams.

In the result there is honor for both boats and for the cities which they represent. The rivalry between the Betsy and the Greene line is healthy and makes for a growing appreciation of the rivers as mediums of sport as well as commerce. The report that a hundred thousand spectators lined the banks and urged on both boats indicates vastly more than merely local interest. They had great sights to witness—the belching smokestacks, the sweating crews, the energy-inspired captains, the daring pilots and, best of all, the boats themselves racing side by side with no choice between them for the whole twenty miles of the course. It is of such epic spectacles that folk lore is made. Much will be heard of the 1929 race of the Betsy and the Tom Greene. Pittsburgh will desire another meeting, regretting most of all that the home waters do not furnish a straightaway course of sufficient length to make a race possible right here.

In a reminiscent and pensive mood over the faded glories of the rivers, the Louisville Courier begins an editorial with an old quotation:

Gangway, catfish! Cross dat bar.

We's a-comin' on de Guidin' Star.

As the black smoke rolled from the twin stacks of the Betsy Ann and the Tom Greene, racing upstream from Cincinnati to New Richmond, the mist of sixty years or more rolled back and revealed to crowds of pleasure-loving moderns in airplanes, motor speedboats, an excursion steamer, and on the banks a revival of one of the most thrilling sports of their grandsires along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

Oh, I wouldn' be a fireman,

He wuks down in de coal;

Ah'd ruther be de gamblin' man

An' wear a ring o' gol'.

The "gamblin' man" was absent as the Betsy and the Greene puffed and strained and shivered from stem to stern, but one might well picture his ghost, attired in a tall beaver hat, high collar and black stock, ruffled shirt bosom, lavender frock-coat and checkered trousers, strapped under his boots, leaning over the rail and waving a roll of bills at the rival boat, offering wagers.

This was no gambling event nor yet a commercial scheme, the winner to get the business, but purely a contest of speed between friendly rivals.

A "Retro-fashions" page from Youth's Companion magazine 6 April 1922. Apparently the young readers of this periodical were both boys and girls. The emphasis in the illustration is on the fancy ante-bellum apparel worn by the ladies on the levee rather than on the steamboats behind the ladies and gents.

"Fine Art" painting as illustrations by Morton Roberts This is the second to the last piece of artwork: Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke on the New Orleans levee in 1920.

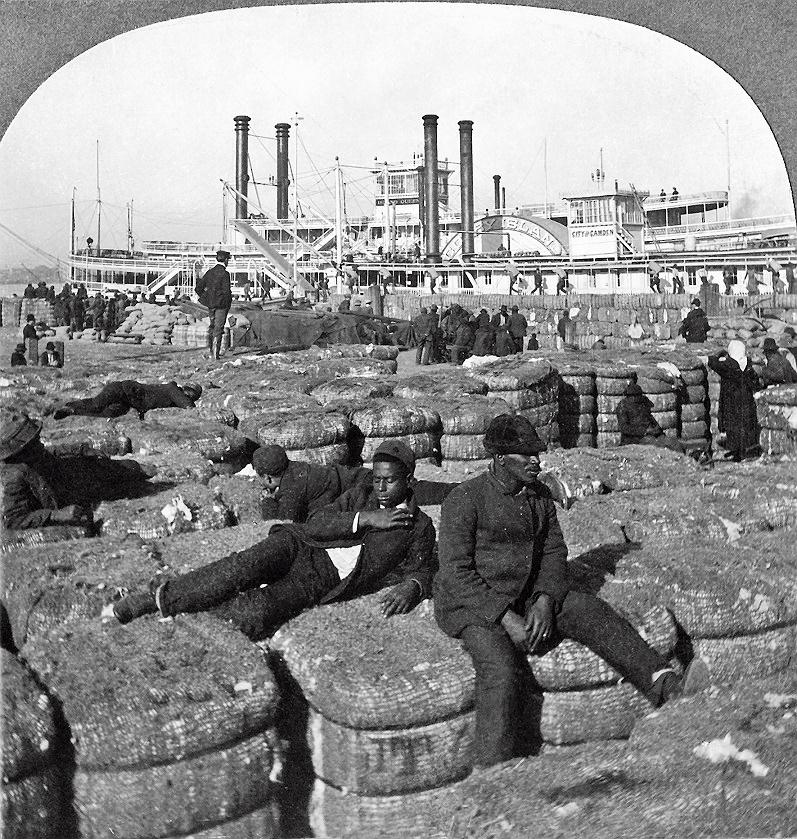

Morton Roberts obviously referred to the Keystone stereoview Number 119 "Cotton! Cotton! Cotton! Levee, New Orleans, Louisiana" of the roustabouts resting on cotton bales while they waited for their next assignment of heavy lifting. Roberts got his steamboat reference from another photo or photos. Maybe I'll come across the source one of these days and add it to this demonstration.

LIFE Magazine

December 22, 1958

U.S. ENTERTAINMENT

Special 2 in 1 Holiday Issue

Beginning on page 64

When Jazz Was Young:

Eleven paintings by Morton Roberts and vivid recollections of old time musicians evoke days when America's own art form was born in New Orleans and rode north of the river.

The caption for the attached painting was a quotation from Louis Armstrong regarding the young Bix Beiderbecke. At the time both musicians played cornets. It wasn't until the mid-1920's that "Satchmo" Armstrong switched to a trumpet.

"I had my first job with Fate Marable's band" (beginning in September, 1918 on one of the Streckfus steamers that conducted excursions around the harbor of New Orleans).

"In 1920 I was 19 and Bix was 16. He just sit there on the levee and listen to me blow and then go home and go to work. Listen, I mean work. I told him just to play and he'd please the cats but you take a genius and he's never satisfied. Later on we'd meet when we played the same town. After we closed the door on the cats we'd get together and have a ball. If that boy had lived, he'd be the greatest." Bix passed on in 1931 at age 28.

Attached scan of an un-numbered page from the 15, May 1945 issue of the Saturday Evening Post In the book of Louisiana and Mississippi plantations that I have there's no exact match for the plantation house so it may have been an idyllic fantasy of a Southern house on the Mississippi River. The steamboat is a fairly generic sidewheeler also but the whole image has charm. The scan enhanced the artwork as it appeared in the magazine quite a bit, now it's "more better." The style of the painting is reminiscent of the backgrounds painted by Disney artists for animated films. Can imagine Alice and Dinah the cat under the tree just before the White Rabbit ran by with his watch saying "I'm late! I'm late! For a very important date!" (in "Wonderland.")

A partial transcript of the "copy" below the illustration:

"Pittsburgh Paints Look Better Longer

Near a great river shadowed by venerable, gnarled oaks, stands a gallant Southern home, ageless and serene. The spirit of warm welcome is ingrained in its architecture. Friendly as a handclasp, the high pillared porch is a harbor of hospitality. Wide, inviting doors are a silent apology for their ever being closed. The spacious hall leads to a sweeping staircase, as graceful as the train of a bride's gown. Mellowed by the light of countless candles and soft southern nights, blessed by years of kindly sunlight, the great homes of the South have an aura of romance. Old mahogany is rich with the priceless patina of time and use. Graceful mirrors recall the gracious days and gala nights when they reflected a stately era of rustling silk, fine linen and gleaming silver. These are fortunate homes that never can he empty because they are well-peopled with memories. Their beauty belongs to all who share the love of home that is deep-rooted in our national character. At no time in history has this great American trait been more evident than now. We treasure our homes and the desire to protect them is common with us all.

. . . We take pride and great satisfaction in making finer products for those who know that a few cents more paid for quality paint is a wise investment.

Time has proven that Pittsburgh Paints do look better longer.

PITTSBURGH PAINTS

PAINTS • GLASS • CHEMICALS • BRUSHES • PLASTICS

Copyright 1948 Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co.. Pittsburgh, PA

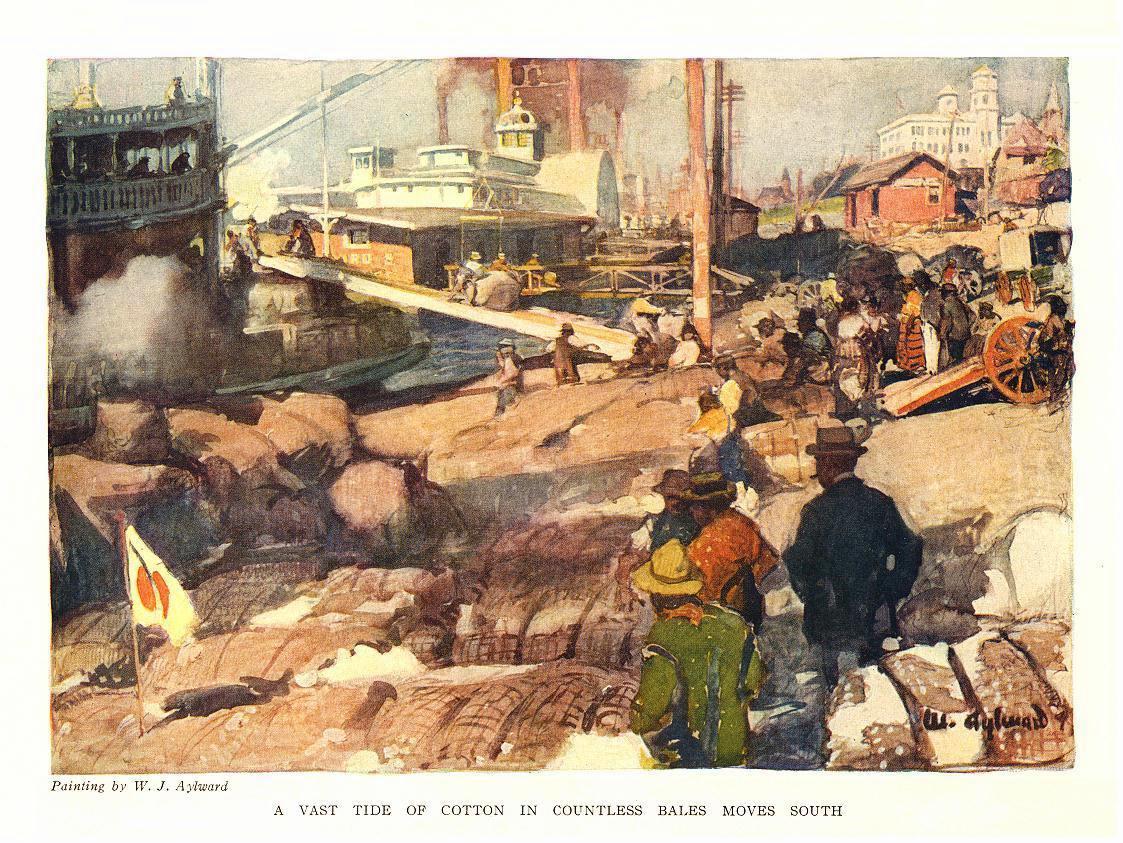

Magazine illustration of Memphis levee by W.J. Aylward 1915.

With the exception of images credited to public institutions,

everything on this page is from a private collection.

Please contact Steamboats.com for permission for commercial use.*

All captions provided by Dave Thomson, Steamboats.com primary contributor and historian.